A depressed comedian does a mental health podcast. The punchline is a profound hour of radio

It’s hard to articulate what depression feels like. When I’m in a pit, everything feels harder, more depleting, a struggle. I’m zapped of inspiration, motivation, creativity — the spark that makes me feel vibrant and alive. When you have depression, it can seem like everyone has it figured out except you. Like you’re flailing and failing, and you’ll never feel balanced again, much less happy enough to thrive and create.

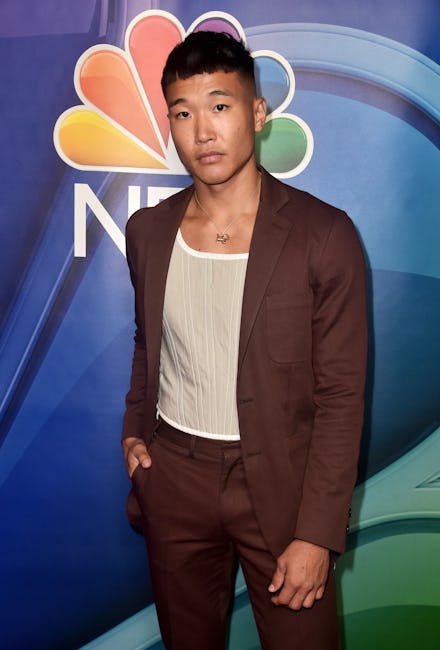

Then when I’m on the upswing, I get “depression amnesia” where I truly can’t quite recall what it felt like living under that boulder of melancholy. When I’m feeling buoyant, productive, sharp and inspired, I figure that’s how “normal” people feel most days. I think that’s one of the many reasons that listening to extremely accomplished and brilliant writer, comedian and actor Joel Kim Booster wallow in the muck of his own shitty feelings on a recent episode of John Moe’s Depresh Mode podcast feels special, even profound. It’s an archive of what depression really sounds like.

Moe asked gentle but probing questions to chisel away at what was going on: Booster said he hasn’t been able to write jokes in a year and a half, since before the pandemic. He’s convinced his comedy career is kaput and he’ll have to fall back on acting. (He says regurgitating someone else’s words still comes easily.) Sixteen months of living through a plague has been traumatic for even the luckiest of us, but Booster tragically lost his dad to COVID-19 this March. Furthermore, the comedian disclosed he was diagnosed with bipolar disorder about two years ago. He suspects his best writing came from manic episodes, and now that he’s medicated, he worries those bursts of inspiration are gone.

My therapist often encourages me to reframe negative self-talk as though I’m addressing a dear friend, since I’d never be as hard on my loved ones as I am on myself. Listening to Booster lament all his perceived shortcomings, I wanted to reach through my earbuds and give him a hug. I wanted to tell him that he’s been through a lot and is doing great in the face of seismic grief and uncertainty. I laughed a little, actually, hearing Booster rattle off all the stuff he’s still managing to get done while mucking through the worst depression of his life. Let’s just say, I’m not as good at balancing work, chores, workouts and socializing when everything feels terrible. (On the flip side, even when I’m in the pits, I manage to keep my plants and dog alive and write multiple articles most days for Mic, so everybody’s baseline is different.)

Booster apologized for being a downer at several points in the interview, and Moe offered to pull back if his line of questioning got too intense. Their 50-minute conversation is barely edited and gets a bit uncomfortable at times; there’s lots of dead air and grasping for the right words. But it’s beautiful and far more impactful than any polished, fakely upbeat episode would’ve been. One terrible thing about depression is that it tends to isolate us in our own cesspool of misery. There’s an understandable impulse to hide it for fear of being “too much” for other people. I’m grateful Booster was brave enough to be transparent. “It is a lot of work to appear normal,” he admits, “and this has been nice to just be a fucking blob of flat emotion.”

Pretending we’re fine when we’re not doesn’t help anybody: not ourselves, and not others who are suffering. The big reminder I took away from this profound hour of radio (other than that I'm not alone) is that we need to talk about depression more often. We have to share honestly and listen to others. It's hard work, but I think it's time to move past self-flagellation and worrying we're dragging people down. We’re not heavy all the time — it’s the depression that’s heavy — but it helps to share the load.