Being honest about your drug use is a crucial type of activism

I am a drug user. So are most of the people I know, but most people keep their use private for fear of the stigma attached. That’s reasonable. There are real repercussions to coming out of any closet. But if we actually want to see an end to the myriad of problems caused by our country’s draconian and racist drug policies — the over policing of Black and Latinx Americans, mass incarceration, and overdose and death due to toxic drug additives — those of us with the privilege of stability could really help by being candid about our own drug use.

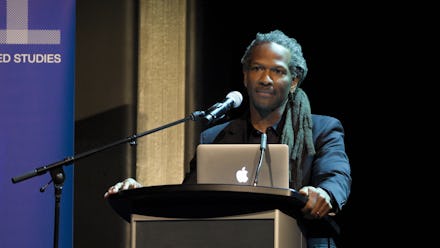

“Respectable middle class people need to come out of the closet,” says Carl Hart, a neuroscientist and professor of psychology and psychiatry at Columbia University, and author of the book Drug Use for Grown Ups: Chasing Liberty in the Land of Fear. “The more people who are vocal about their drug use, we, as a society, will become less likely to vilify people for what they do with their bodies.” At its root, this vilification is fueled by the stigma around using certain types of drugs. To be clear, Hart doesn’t espouse his wisdom from the sidelines. Not only has he been a highly regarded expert in the field of addiction for more than two decades, Hart is also a heroin user.

Take a moment with that. And also, go ahead and read some pearl-clutching headlines about Hart’s heroin use. As you can imagine — because heroin has a different connotation attached to it than, say, weed — being open about his drug use has not exactly been a comfortable experience.

“People have said some hurtful things,” he tells me. Still, Hart believes that the social good created by coming out of the chemical closet is worth the personal repercussions. “We’re not that important as individuals,” he says. “Think of all the people who put themselves on the line...sometimes what they did didn’t make much of a difference in their own lifetimes, but their examples are there for everyone else to see.”

Hart says that LGBTQ and Black civil rights movements were the inspiration for him to write Drug Use for Grown Ups. In his book, Hart urges drug users who can socially afford to come out of the chemical closet to do so as a form of mass protest. “If more people followed this advice,” he wrote, “it would be extremely difficult to pigeonhole all users as irresponsible, troubled members of our society. I urged them to get out of the closet and blatantly disregard laws that prohibit drug use, because such laws are ruthlessly unjust.” Hart considers his heroin use as a way to exercise his right to pursue pleasure and argues that using substances that bring us enjoyment should be a protected right, akin to any activity that we do in the pursuit of life, liberty, and happiness.

If this shocks you — or even if it comforts you, it’s important to address what we’re dealing with as a society: Too many of us have been trained to see drug users in black and white — both metaphorically and racially. Most people think of drug users as either Black and poor in the ghetto or white and rich in Ibiza. We have a cultural tendency to associate different drugs with different types of people and then deem some acceptable and others deviant. Xanax and weed are generally seen as pretty okay middle-class coping mechanisms, while crack and heroin are looked down on as hard drugs that dangerous Black people take.

The reality is a lot more grey. If we start seeing drug users as fellow members of our shared society, Hart argues in his book, we will all work harder to keep them safe from persecution and prosecution. The current laws that criminalize certain substances have led to the mass incarceration of Black and brown people for non-violent crimes and therefore the deterioration of many people’s lives, families, and social structures.

Protecting drugs users also means regulating drugs in a way that ensures the safety of the drugs that people take, educating the public about drug-related issues, and giving law enforcement evidence-based training in drugs so that they are more likely to protect and educate users instead of punishing or harming them. Fear of punishment and a lack of knowledge about what’s actually in the drugs that people are taking are both major threats to people who use drugs.

The prohibition of drugs like heroin and cocaine means that people who do take drugs are forced to get them on the black market. While people with privilege may have access to “cleaner” substances, the drugs people buy on the street are often laced with fentanyl and other toxic compounds. It’s those additives that are thought to be the cause of many cases of overdose and death, not the original substances — like heroin — themselves.

In addition, illegality and over policing lead many people to hide their use. People who want to take IV drugs don’t have access to safe places to use or clean needles to use with. Even though research shows that needle exchange programs and fentanyl test strip distribution are effective in saving lives, there are still laws that prevent these common sense reforms.

Right now, most people have a binary notion of substance use. It’s like there are two kinds of people: addicts and everybody else. The problems that false polarity creates are both systemic and personal. I went through a period of time a few years ago when I misused opioids. I thought that meant that I was “an addict,” and so I came out as an addict.

I lost friends and jobs because I was an addict. It’s taken me years in recovery and hundreds of hours of therapy and research for me to come to the conclusion that, actually, I’m not an addict, but I’m not “everybody else,” either. Who I am is a person that uses drugs sometimes, mostly responsibly, sometimes not. That nuance has often been lost, though, on potential employers — and sometimes potential dates — who google me and write me off as a junkie.

Since I stopped actively “doing” 12-step addiction recovery, I have been working to de-stigmatize drug use. We’re going to have to get more refined in our thinking if we want to shift the conversation away from “helping those poor junkies,” and start nudging people towards a conversation about how to actually make drug use safer and create drug laws that aren’t just tools for policing already overpoliced populations. And that means that some of us need to stop apologizing for our “bad” behavior and start insisting that it’s normalized.

It doesn’t seem like an accident that interest in the opioid epidemic is due to the fact that opiates are seen as a “white” drug. Republican leaders and presidential candidates like Chris Christie have leapt up to say that they know or love someone who has dealt with addiction. While certainly still stigmatized, this perception of who the “victims” are has shaped the laws. This is a far cry from the demonization of the (Black) "superpredator" promoted in the crack era. The reality is that there is a vast distance between “victim” and “superpredator,” and most of us live in that as yet undefined space.

We have to stop requiring people who admit to using drugs to bend and scrape before us. “We really care about people who are contrite,” Hart says. Yes. Everyone loves a pretty white victim who’s really really sorry they got strung out. What we need, Hart argues, are people who are unapologetic about their right to use drugs, even if they can only show that courage in front of a few people.

You don’t have to, say, write a whole book that systematically debunks all the logic behind this nation’s drug policies or start a podcast about your crack habit. “How big an audience doesn’t matter,” Hart says, “The point is that people should come out of the closet.” As a person who has come out of many closets, I can tell you that what you often find is that while you felt alone inside the closet, there’s a lot of other folks on the other side of the door waiting for you to have the courage to join them.