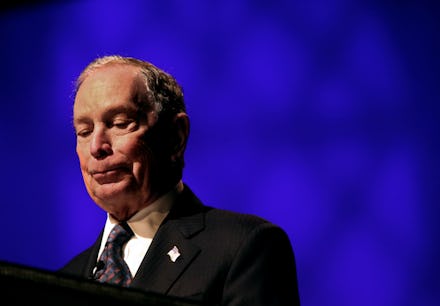

Michael Bloomberg finally apologized for stop-and-frisk. That won't be enough for 2020

Over the weekend, Michael Bloomberg, the former mayor of New York City, reversed course on one of the defining issues of his mayoral term — the stop-and-frisk policies he supported and expanded during his term in office. Under stop-and-frisk, police searched hundreds of thousands of almost exclusively minority people on the street, looking for guns or drugs. A whopping 88% of the searches did not lead to an arrest, meaning that overwhelmingly, individuals who were stopped and assailed by police had done nothing wrong at all.

“Over time I’ve come to understand something that I’ve long struggled to admit to myself,” Bloomberg said, speaking to a crowd at a church in Brooklyn, New York. “I got something important really wrong. I didn’t understand that back then, the full impact that stops were having on the Black and Latino communities. I was totally focused on saving lives, but as we know, good intentions aren’t good enough. … I want you to know that I realize back then I was wrong, and I’m sorry.”

Notably, Bloomberg has been publicly teasing a 2020 run for the Democratic presidential nomination. While he was New York City’s chief executive, however — his term spanned from January 2002 to December 2013 — the number of stops per year ballooned into the hundreds of thousands, reaching a high of 685,724 in 2011 before declining to 191,851 in 2013. At the time, both police and the communities most affected protested that the policy was having disastrous consequences.

On Sunday, police union leader Patrick Lynch attacked the mayor’s apology, per the New York Post, saying that Bloomberg “could have saved himself this apology if he had just listened to the police officers on the street” at the time. “We said in the early 2000s that the quota-driven emphasis on street stops was polluting the relationship between cops and our communities,” Lynch added.

Stop-and-frisk was an extension of the “broken windows” theory of policing that came to prominence in New York under Rudy Giuliani, Bloomberg’s mayoral predecessor. That notion centered on the hypothesis that cracking down hard on small infractions could lead to drops in more serious crimes. In practice, though, it turned poor neighborhoods into dystopian surveillance states, where people could be stopped and searched by police after school or work without having done a single thing wrong.

Even as crime began to drop precipitously in New York, Bloomberg refused to curtail stop-and-frisk, arguing that crime would rise again if he did. Damningly, after Bloomberg’s successor Mayor Bill de Blasio heavily cut back on stop-and-frisk, crime continued to fall.

“He was wrong because he never listened. He didn’t even acknowledge the validity of concerns, again as part of his often haughty nature," de Blasio said in an interview with BuzzFeed News. While Bloomberg is mulling an entry into the 2020 race, de Blasio’s own run has already flamed out.

Bloomberg’s change of heart on stop-and-frisk is very recent. He was defending the policy as recently as January of this year, when he said that officers "certainly did not pick somebody by race" to confront. Instead, he insisted, police focused on "kids who might have a gun," with the goal of “keeping kids from going through the correctional system.” But in 2011, of 685,724 NYPD stops recorded, 53 percent were of Black people and 34 percent were of Latino individuals. Only 9 percent were of white people.

Bloomberg has recently filed to appear on the ballot in Democratic primaries in Arkansas and Alabama, and his apology seems to many to be an attempt to win over the Black voters whose support he’d need to have a chance. “Bloomberg’s cynicism here is staggering,” wrote progressive pundit Charles M. Blow in The New York Times. De Blasio said the apology has an "obvious convenience."

Whether or not Bloomberg, who has not yet formally announced his candidacy, is successfully able to overcome stop-and-frisk, it’s clear that it’s going to be a tough PR battle for him to fight. This lines up with a trend throughout the Democratic primary so far: Candidates’ criminal justice records have proved to be powerful litmus tests for progressive voters.

California Sen. Kamala Harris centered her campaign around her experience as attorney general of California, claiming it gives her the prosecutorial background to go after Donald Trump in the general election. She’s struggled, however, to overcome the perception that she’s overly zealous on crime.

Vice President Joe Biden, too, has faced tough questions about his support for the Clinton administration’s harsh 1994 crime sentencing bill. “I haven’t forgotten that it was just this year, as he was about to enter the race, that Joe Biden finally offered a full apology for the disastrous 1994 crime bill,” wrote Blow.

Mayor Pete Buttigieg has also faced scrutiny about police treatment of minorities in his city of South Bend, Indiana. Residents complained that he mishandled a June 2019 case where police shot and killed a black man named Eric Logan. “Stop using [the shooting] for your own personal agenda,” said the victim’s brother at the time.

While much of the energy in the primary has been centered around health care, criminal justice has emerged as one of the underlying issues separating the moderate and progressive wings of the Democratic Party. For a lot of voters, especially those from minority communities that have been most adversely affected by police brutality, criminal justice is a core concern when evaluating candidates. That pressure is evident in Bloomberg’s swift about-face on stop-and-frisk — and he’ll need to swim a lot farther upstream on the issue if he wants to win.