'Sound of Metal' is a heartwarming — and frustrating — take on deafness

Whenever I meet a hearing person, I immediately begin steeling myself for their inevitable release of what I like to call “the triad of microaggressions”:

1. Incredulity at deaf independence (“You can drive?”)

2. Comparison to animal (“Oh, my cousin has a deaf dog!”)

3. Intimation that death is preferable to deafness (“I would just die without music!”)

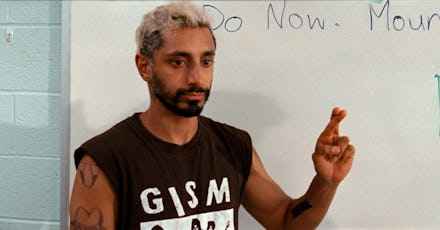

It’s this third idea — that deaf people couldn’t possibly enjoy music and are somehow the lesser for it — that fuels the opening sequences of the film Sound of Metal, written and directed by Darius Marder and starring Emmy award-winner Riz Ahmed. The movie, which premiered at the 2019 Toronto International Film Festival and was released on Prime Video last month, has been the subject of significant awards buzz, with Ahmed taking best actor at the Gotham Awards for his turn as Ruben, a drummer in a heavy-metal duo with his singer girlfriend. Much of the praise for the movie has centered on Ahmed's electric performance, the film's inventive sound design, and its attempt at authentically representing the Deaf community. And while the film's approach to addressing the complexities of deafness is a step forward, the shortcomings are still evident.

The story begins with Ruben and Lou (Olivia Cooke) in the RV they use to tour the country, playing ratty, hole-in-the-wall venues where you might find the musicians offstage helming the merch table. When they're not rocking out, Ruben, now four years in recovery from drug addiction, is focused on his health, exercising and blending green smoothies for himself and Lou each morning. Then one night, the sudden and unexplained onset of Ruben’s severe hearing loss threatens to upend their bohemian setup. Worried over a stress-induced relapse, Lou brings Ruben to a bucolic recovery program for deaf people, headed by a crotchety Vietnam vet named Joe (Paul Raci). There Ruben spends his days learning American Sign Language and working with deaf children as he struggles to accept his new circumstances.

I’m a big fan of Riz Ahmed, so when I found out he’d be “cripping up” — the all-too-common practice of a nondisabled actor taking on a role meant for a disabled person — I was disappointed. And while I still believe any number of talented deaf actors could have played Ruben, certain aspects of the character make this casting choice more palatable than other examples of hearing people playing deaf. Like Ahmed, Ruben is an outsider in Deaf culture and new to the experience of deafness, and the fact that Ahmed himself spent seven months learning ASL mirrors the process the character goes through. More frustrating is the casting of Raci as Joe. Although Raci is a member of the Deaf community as a CODA (child of a deaf adult), his casting still feels like a missed opportunity in a film where Deaf actors are otherwise relegated to the background.

What we do see of the deaf people in this film is well-rendered. Deaf actress Chelsea Lee shines in her limited screen time as confidant and fellow resident, Jenn. And Jeremy Lee Stone, Ahmed’s ASL instructor both on and offscreen, provides firm and immersive lessons peppered with humor, the way I wish all ASL students were taught.

Stone’s work no doubt gave Ahmed the tools he needed to put in such a strong performance in this film, but I can’t help wondering if there should have been more consultation with deaf people about this project earlier in development. For instance, if music was Ruben’s livelihood and lifeblood, why would he give up on it so quickly? We see only one night of him trying to play the drums after the onset of his hearing loss. Couldn’t he have tried… practicing?

This is the element of the movie that smacks most of hearing misconceptions about deafness. From the all-deaf hard rock band Beethoven’s Nightmare to d/Deaf singers Mandy Harvey and T. L. Forsberg, to rapper Sean Forbes — who made history last year as the first deaf person to break the Billboard Top 200 — musical performance is far from an impossibility. For many deaf people, including myself, the experience of music is strongly tethered to vibration, an opportunity that seemed rife for exploration in a movie about a drummer.

The movie rightly highlights that deafness is not about silence. The focus on muffling and distortion are important educational moments.

The more disconcerting plot choice for me — mild spoiler warning — was Joe’s decision to banish Ruben from the program after he chooses to get cochlear implant surgery. While it’s true that we don’t view Deafness as a handicap, the harshness of this move rang false. The idea that one can either be culturally Deaf or have an implant is a position I’ve found to be touted far more frequently by medical professionals perpetuating misinformation about the detriments of bilingualism, rather than by the Deaf community. As a vehicle for moving the plot forward it works; unfortunately, the more the myth that cochlear implants and ASL are mutually exclusive is spotlighted, the more children are harmed by the social isolation and language deprivation that can result from taking an oral-only approach to deaf education.

Where the movie does shine is in its portrayal of the physical experience of hearing loss and cochlear implant use — it’s no surprise that there is Oscar talk for the sound design here. The movie rightly highlights that deafness is not about silence, so the focus on muffling and distortion, and the overwhelming and even unpleasant sensations Ruben experiences while using his implants are important educational moments. Cochlear implants are often misconstrued as a miracle cure, so seeing the ways in which Ruben — a best-case scenario user in that his brain already knew how to hear — struggled, was no doubt eye-opening for a lot of hearing viewers. These were also, though, moments in which I was reminded most that this movie was not for me; repetitive closed caption descriptions of “distorted sound” provide little emotional benefit for a deaf viewer.

Nevertheless, that Sound of Metal refuses to romanticize deafness is perhaps its greatest strength — there are no saccharine Mr. Holland’s Opus moments here. The movie also avoided actual romance as a tool for helping Ruben feel comfortable in his new life, a potential plotline I feared when the ever-radiant Lauren Ridloff first appeared as Deaf school teacher, Diane.

Sound of Metal is at its best when it’s pushing back against stereotypes, deaf-related and otherwise, and is certainly a step in the right direction with respect to encapsulating the complexities of deafness, and even making strides toward authentic casting. If I find it grating that the film is not made for a viewer like me, it helps to remember that it isn’t about me, either — this isn’t a movie about the Deaf community at all. Deaf and hard-of-hearing people who struggle to find their place between two worlds deserve to see themselves onscreen, too. And seeing Ruben realize that deafness is in a way the solution, rather than the root, of his problems — which have been lifelong — is an added bonus. Overall, this film’s take on deafness is incomplete, sometimes heartwarming, other times frustrating, and never tidy — you know, kind of like learning to find yourself.