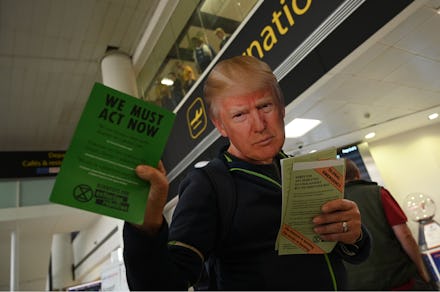

There are a lot of similarities between climate change deniers and coronavirus skeptics

When Donald Trump was first presented with the potential threat of coronavirus, he dismissed it. In an interview on CNBC, he described the outbreak as "one person coming in from China" and said that the situation was "totally under control." Behind the scenes, it seems he was equally dismissive, even in the face of intelligence warnings acknowledging the threat of a pandemic. While the president has changed his tune recently — extending social distancing guidelines through April 30 and acknowledging that coronavirus could claim hundreds of thousands of lives — he and his administration came around on the science too late. The months of downplaying the pandemic in public and ignoring experts undermined the country's response — but it's also what came naturally to a president and his cohorts who have spent years denying the effects of climate change.

Trump has been one of the most vocal climate skeptics around for nearly a decade, dating back to 2011 when he started claiming things like snow in October debunked the concept of global warming, or that climate change was a hoax "created by and for the Chinese" to hurt manufacturing in the US. Prior to his heel turn on science, Trump actually encouraged businesses and governments to take action to address climate change — even signing on to a full-page ad in the New York Times advocating for urgent action in 2009. So what changed over the two years that Trump went from pushing for sustainability to pushing conspiracy theories? Around the same time Trump started spouting off about how climate change is bogus, he also took on a new gig as a regular commentator on Fox and Friends.

Climate denial has run deep in conservative media since the early 1990s. While it's a heavily partisan issue now, climate change was not always controversial. As recently as the early 1990s, polls showed that about 80 percent of Americans knew of and believed in climate change, and believed that it needed to be addressed. Around that time, fossil fuel interest groups started to crop up with the intention to sew doubt among the majority of Americans who acknowledged the threat of climate change. Through massive spending campaigns that targeted media, policy makers, and educators, these groups started planting the idea of "uncertainty" surrounding the underlying science that showed the reality of climate change. At the same time that these disinformation campaigns were underway, conservative talk radio was exploding and characters like Rush Limbaugh were looking for new ways to hook listeners. Limbaugh targeted climate change and branded himself as an "unofficial spokesperson" of global warming deniers. He was joined quickly by Fox News, which played host to a number of conservative personalities that picked up Limbaugh's anti-science talking points and ran with them.

The result of these efforts started decades ago are evident today. Climate change, once a nearly-universally agreed upon subject, suddenly became a partisan issue. According the Pew Research Center, the divide on climate change in 2020 is as wide as it's ever been: 78 percent of self-identified Democrats believe climate change should be a top priority, compared to just 21 percent of Republicans. While it's not quite as stark a political divide, polling shows that the science skepticism of Republican voters has carried over into opinions on coronavirus. According to an ABC News/Ipsos poll, 87 percent of Democrats are concerned about the spread of coronavirus, while just 66 percent of Republicans feel the same level of worry.

It's not just the polling that reflects this split. The arguments coming from many conservatives, including the president, about coronavirus echo the talking points that have been central to their climate skepticism for decades now. "There are many similarities between the types of arguments climate change skeptics and coronavirus skeptics make," Dr. Emma Frances Bloomfield, assistant professor of communication studies at the University of Nevada, Las Vegas, tells Mic. "Both types of skeptics will make arguments about the ability of scientists and experts to make predictions and interpretations from models." For instance, people within the Trump White House reportedly decided to ignore the predictions of the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention and instead started circulating a model from the Hoover Institute that projected only 500 Americans would die from coronavirus — a figure that has already been surpassed. Dr. Bloomfield said skeptics will often interpret difficulties in modeling "as reasons to distrust statements by those experts overall."

Another common trope among those who have tried to downplay the threat of the coronavirus pandemic is the idea that the economy can't just shut down – that "shelter in place" policies are actually an attempt to cripple the economy and tarnish Trump's successes. Dr. Bloomfield says these arguments mirror climate deniers who claim scientists are simply profiting off environmental research. Likewise, there are links between the climate skeptic's argument that environmental rules limit personal freedom and the pushback from coronavirus skeptics who feel quarantines are too onerous and limiting. "I see many arguments emerging online regarding people's personal rights to congregate, leave the house, and even to not wash their hands as justification to avoid CDC recommendations," Dr. Bloomfield says.

These arguments are playing out at an accelerated rate compared to conversations about climate change primarily because this crisis is moving much faster. Even the president has jumped from argument to argument over the last few months — outright denying the outbreak at first, then downplaying its effects, then suggesting the pain of shutting down the economy was too much to bear before finally coming around to the science that was put in front of him. It's not clear if his supporters will follow, though conservative media has certainly made a tonal shift over the course of the last few weeks. Fox News has largely stopped pretending there is no threat and has even parted ways with Trish Regan, a host who claimed that coronavirus concerns were just part of an "impeachment scam" worked up by the Democrats to try to hurt the president.

Convincing science skeptics on any topic is a challenge, but Dr. Bloomfield has some advice for how to get through to those in your life who may not be taking coronavirus seriously. "The primary strategy I suggest is to have a dialogue with people about their concerns and why they think the way they do, to understand their obstacles to agreeing with and believing the experts," she says. "For example, if someone doesn't trust the CDC to provide accurate numbers, you might ask who would be in a better position to provide those numbers? You could also locate an authority that the person does trust and show overlaps between that person and the operating medical advice." She also recommends storytelling rather than just facts and figures. "While statistics can give startling information about the breadth of the pandemic, anecdotes can personalize and humanize the pandemic and put names to those statistics of people who are being hospitalized and even killed." She notes that she has seen some science skeptic online communities looking for people who have been affected by coronavirus as they try to get a sense for how real the threat is. "This idea that coronavirus is intangible and doesn't affect us personally (something that comes up with climate change as well) can be countered by sharing personal stories," she says.