These revolutionary sex shops offer a refuge for marginalized people

When I was growing up in the early aughts, my hometown’s sex shop had a reputation as a seedy establishment from which customers emerged, purchases in an opaque black plastic bag, casting furtive glances. Now, a new generation of these stores has emerged, and they’ve evolved into more than nondescript buildings where you can buy toys in secret. These sex-positive shops not only sell products that enhance people's sexual experiences, but empower their communities and provide spaces where LGBTQ individuals, people of color, and those who live at the intersections of these identities feel safe.

I asked an expert about the evolution of the sex shop — Lynn Comella, an associate professor of gender and sexuality studies at the University of Nevada, Las Vegas and author of Vibrator Nation: How Feminist Sex-Toy Stores Changed the Business of Pleasure. The owners of these more progressive sex shops, many of whom are marginalized themselves, are deeply engaged on a local level, Comella says. They host workshops on consent, donate their goods to raffles, and advocate for sex work legalization. These LGBTQ, POC-inclusive businesses are home-grown, grassroots operations, launched in response to unmet needs unique to their communities.

Especially amid threats to the rights of LGBTQ and POC communities under the current administration, these spaces are crucial. They “can serve for many people as a refuge,” where they’re accepted and don’t need to worry about drawing stares, being asked to leave, or justifying their existence, period, Comella says.

Here, they can forget the political climate, at least for a moment, and “not only buy product but have an entire encounter around sexuality.” Engaging with the products might prompt them to talk about their sexual pleasure, for instance, which could segue into a fantasy they hadn’t felt comfortable voicing before.

These LGBTQ-, POC-inclusive businesses are home-grown, grassroots operations, launched in response to unmet needs unique to their communities.

To be fair, progressive, feminist-owned sex shops like Good Vibrations and Eve’s Garden have existed since the 1970s, Comella tells Mic. They, too, saw vibrators as tools of liberation that could help women learn what they liked, allowing them to enjoy greater sexual fulfillment. But their offerings, and therefore their clientele, mirrored the primarily white, cis, hetero, middle-aged women who founded them.

As more entrepreneurs from marginalized communities opened sex shops, they looked to these predecessors as models, but questions about queer and trans desire, as well as racial inclusion, figured more prominently in their business models, as they did in their own lives. They’ve tended to cater to a more diverse clientele as a result.

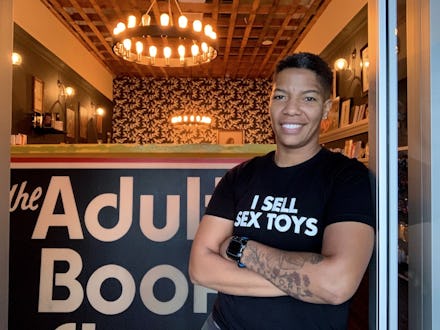

Nenna Joiner’s journey to launching one such store, Feelmore, began when they moved from Las Vegas to the San Francisco Bay Area. Their exposure to conversations among locals about their bodies prompted Joiner (who uses they/them pronouns) to examine their relationship with their own.

After initially selling sex toys out of their car, Joiner opened Feelmore in Oakland in 2011 to heal themselves and their Black community from trauma, especially around kink. “That’s so connected to slaves, corporal punishment, and the military,” they tell me. They wanted to create a space for themselves and other Black Americans to own their sexuality and discover what it means outside of slavery and building families, where they could “talk about the joys of sex like other communities.”

Black and brown customers have told Joiner they feel safe buying from Feelmore, knowing it’s a Black-owned business staffed entirely by people of color. Feelmore allows returns for defective products, whereas most sex shops make all sales final, showing just how attuned Joiner is to these communities. Say a woman rides public transit for an hour or more from Hunter’s Point, a predominantly Black neighborhood in San Francisco, to Feelmore to buy a toy, only for it to break. Joiner believes consumers like her deserve a refund, given the time and money it cost for her to not only make the purchase, but the travel to the store to do so.

Feelmore — which recently opened a second location in Berkeley — is also heavily involved in local advocacy, especially around supporting sex workers. The store has hosted a Q&A with sex workers called “Ask a Ho” to not only educate people who want to enter the sex industry, but dismantle the stigma and myths surrounding it. Joiner also distributes condoms to the sex workers in the area around the store.

Another issue that Joiner and their staff are tackling is homelessness, which has reached staggering levels in Oakland and other cities in the San Francisco Bay Area. They’ve volunteered at homeless encampments, and help people find housing, including those who’ve talked to them in the store about their housing struggles. “I have time. A part of having time is using it toward someone else’s happiness,” Joiner says. “It’s not just about sex toys.”

Like Joiner, Jennifer Pritchett (who goes by JP and uses they/them pronouns as well) created the sex shop they themselves needed. Smitten Kitten, an education-based store they opened in 2003 in Minneapolis, sells non-toxic, ethically-made toys, so no customers have to endure the skin irritation or other bad experiences JP did after unknowingly buying toxic products years ago.

Their experience voraciously reading the books in their college’s LGBT center library inspired Smitten Kitten’s lending library, which carries titles on everything from BDSM and polyamory, to transgender sex work and sexual violence survivorship — “books that might not be available at your local library, stuff people would be embarrassed to take out,” JP explains.

Smitten Kitten offers a bunch of other community resources, too, including workshops on consent, the anatomy of arousal, and anal play, and flies in educators from outside the Midwest, such as Joan Price, who recently taught a class to seniors about sex after a partner dies. The store also donates money, products, and time to fundraising efforts for queer and trans communities.

Indeed, inclusivity is pretty much baked into everything Smitten Kitten does, JP tells Mic. All its staff members “are marginalized in one way or another,” they note. The space is built with accessibility in mind, and the store even offers sex education in American Sign Language.

Beyond Smitten Kitten and Feelmore, other progressive, inclusive sex shops have cropped up across the country, including Sugar in Baltimore, Self Serve in Albuquerque, and She Bop in Portland. But while there’s been a steady increase in these businesses, there hasn’t been an explosion of them, largely because of the many challenges they face — which also makes their future tenuous, Comella says. “These are not easy businesses to start.”

Not only are brick and mortar retailers in general struggling in the age of online shopping, but banks typically don’t loan to sex toy stores, forcing many entrepreneurs to max out on credit cards or borrow money from friends and family. Landlords tend to be reluctant to rent to them, too. (It took about five years for Joiner to secure a space for Feelmore.) Zoning regulations often restrict them to desolate industrial areas, and owners frequently need to negotiate with community members who feel uncomfortable with a sex shop opening up in their neighborhood.

While it’s easier than ever to buy sex toys on Amazon, these spaces are still relevant, and their benefits ripple beyond the marginalized communities who find refuge in them, their owners argue. For starters, they help people communicate about sex in an accurate, honest way — “a life skill, whether it's talking to your kids about sex, or your doctor,” JP says. And with people of color underrepresented in business management, it’s important for communities of color to see stores like Feelmore under management that looks like them, Joiner says. “That has an impact, showing up in your community and making sure you’re open every day, and people seeing that.”