When being the child of immigrants means feeling forever financially indebted

I opened the black leather check holder the server had set on our table and winced inwardly. Outwardly, I pulled my purse out of my wallet and chirruped, “We’ve got it, dad,” with a dismissive wave of my hand. By “we,” I meant my youngest sister and me, who were visiting our parents in the sleepy northern California suburb where we’d grown up, and had grabbed dinner with them at a Thai restaurant. Our meal had come out to more than $150.

My sister, who had a well-paying job in advertising at the time, could afford to split the bill. Me, not so much. As a newly-minted freelancer, I was still struggling to find steady work. Nervous that charging my debit card would result in an overdraft, I tucked my credit card into the check holder — even though it had around $3,000 in debt on it.

I realize any other adult might’ve also experienced shame over not being able to treat their parents to dinner. But this shame is often magnified in second-generation immigrants like me. For most of my life, I’ve felt a deep sense of financial indebtedness to my parents — an obligation to repay them for the immense sacrifices they made to give me the opportunities they never had.

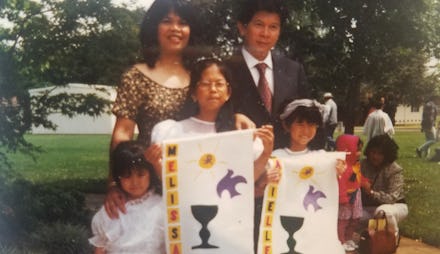

Not once did my parents make this debt explicit or hold it over me. But I knew what they’d sacrificed from the stories they’d told me. More than 40 years ago, they left behind everyone and everything they’d ever known — my dad, to come here from Indonesia, and my mom, from the Philippines. My father clocked in long hours at his telecommunications job and night school so we could gradually upgrade from a basement in Brooklyn to a house outside San Francisco. Meanwhile, my mom raised my two sisters and me largely on her own, far from family who could’ve supported her.

I’ve pretty much always known I wanted to be a writer. But whenever I broached the possibility of writing for a living with my dad, his response was the same: “Do it as a hobby,” he’d say, his tone gentle yet firm. “Become financially stable first. Then you can write as much as you want.”

He nudged me toward majoring in molecular and cell biology in college, and I obliged. Even if I would’ve preferred to major in English, biology indulged my curiosity, and I had a knack for it. Plus, it would allow me to fulfill premed requirements so I could apply to med school, my dad pointed out. And even if I didn’t get into med school, I could still land a high-paying biotech job. My mom, who stayed home since having kids, was mostly absent from these conversations, leaving the career guidance up to my dad.

Majoring in molecular and cell biology left me hollow and unfulfilled. So did working in a research lab after I graduated from college. But as soon as I felt myself doze off while studying for a midterm, or tempted to slack off at my lab job, memories of my parents’ sacrifices loomed over me, casting a long shadow of guilt. They’d given up so much, all so I could enjoy a middle class upbringing, opportunity at my fingertips. Compared to the poverty they’d endured, I had it good; I had zero excuse not to find a lucrative job in medicine so I could pay it forward and support them. Heeding (distinctly American) exhortations to “do what you love” felt selfish.

I could only grit my teeth for so long, though, and I couldn’t imagine a life without writing. One night, after spending hours troubleshooting an experiment, my stomach twisted in rage at my parents — then at myself for daring to villainize them, after all they’d done for me.

But then I wondered: What would it really take to repay them? Could any dollar amount ever reflect what they'd sacrificed for me?

I realized then that my debt to them, by nature, could never be repaid, monetarily or otherwise. And if I kept grinning and bearing it at my lab job, my resentment toward them would only deepen. The best I could do to ensure their sacrifice was worthwhile was embrace the sense of possibility that drew them to America in the first place — to build a life I wanted, a privilege they never had.

Heeding (distinctly American) exhortations to “do what you love” felt selfish.

I approached my dad about my decision to apply to journalism school while visiting him and my mom one weekend, at the dining room table after we’d finished dinner. I steeled myself. “Dad? I need to tell you something.” His eyes flicked from CNN to me.

“I’m applying to journalism school. I’m a mediocre scientist, dad — I’d rather be a successful writer.” I looked up from the napkin I was nervously folding and unfolding. “My teachers and professors have told me I’m good. I’m really good, good enough to do this professionally.”

He was silent, his expression thoughtful. Then: “Okay,” he said, nodding. “Okay.”

After journalism school, I worked as a staff writer for a few years before going freelance, desiring, well, even more freedom. But guilt gnawed at me again as my work began at a trickle. Occasionally, especially when a payment arrived late, I had to borrow money from my dad and sisters to make rent on time, a privilege I’m thankful for every day.

After my parents’ painstaking efforts to shelter me from poverty, here I was, running head-first into it. At nearly 30 years old, it was my turn to support my parents; I felt like I’d failed them.

But I had to trust myself the way my parents did when they immigrated to the US. I had to tell myself that this would be temporary — and it was. Over the next two years, I amassed a stable of regular clients. Now I can afford to pay rent and even spot my family when necessary.

And I try to keep my promise to make my parents’ sacrifice worthwhile. I take Ann Friedman’s advice to "put the 'freedom' in freelance," writing from as far away as Japan and Australia. Both my parents, to my surprise and delight, have expressed happy disbelief at this possibility.

I spoke with psychologists about how to deal the next time I experience this guilt. For Margarita Alégria, a professor of medicine and psychiatry at Harvard Medical School, reconciling guilt as a child of immigrants largely boils down to communication.

One approach is to ask my parents how I can help them, being clear about what I can and can’t do. In other words, I could’ve avoided miring myself even further into debt that night at the Thai restaurant if I’d had a candid conversation with my parents beforehand about what they expected from me financially. I doubt they would’ve wanted me to spend money I didn’t have.

Alégria also suggests exploring what my parents consider career success or failure. “Many times the vision of what parents want as success for their children might be totally different from the success you might be envisioning,” she says.

About a year ago, I asked my dad what his biggest worry was for my sisters and me. We were seated, again, in the dining room in the house where I grew up. His knotted hands folded in front of him, he said he was scared that we would struggle the way he did when he arrived in the US. He hoped we'd be successful — but to him, that didn't necessarily mean earning tons of money. Ultimately, he wanted us to be happy.

On some level, I’d always assumed he'd pushed me toward medicine so I could repay him and my mom for all they’d done for me, when really, he just wanted to protect me from living with the constant uncertainty they did. In another conversation, he explained that he swayed me from writing because, as someone who didn’t grow up here, he couldn’t imagine what a steady writing career would look like. On the other hand, he knew what a medical or biotech career looked like; they felt safe. If only I'd spoken with him about all of this sooner, I thought.

Maybe feeling financially indebted to my parents isn’t such a bad thing. “You could look at this as unhealthy feelings of guilt, or you could look at this as a way you enact and wear your love for your parents,” says Anna Lau, a professor of psychology at UCLA.

Now that my guilt no longer veers into resentment, or burdens me financially, maybe I can observe and accept it as part of how my experiences have shaped my emotional life, she adds. I’ve accepted that my parents did their best; maybe I need to practice the same acceptance with myself.