SCOTUS sides with Republicans in limiting mail-in ballots in Wisconsin, a key battleground state

Wisconsin voters need their mail-in ballots to arrive by 8 p.m. on Election Day to be counted, the Supreme Court decided late Monday. The high court refused to take up Democrats' challenge to a lower court ruling that denied voters a buffer of six days following the election to allow their Wisconsin absentee ballots to arrive without being considered late. With just seven days to go before the election, this determination could have consequential impacts on the general election results not just in Wisconsin, but nationally.

Monday's decision by the Supreme Court was a 5-3 ruling for the conservative majority. (It also coincided with the confirmation of Judge Amy Coney Barrett to the bench, but her first day as a justice is Tuesday.) It's the latest in a patchwork of disparate election laws governing how voters in each state must cast their ballots. The court offered a "state's rights" justification for allowing the lower court's decision to stand, saying that if the eight-person bench took up the case it would constitute a "federal intrusion on state lawmaking processes."

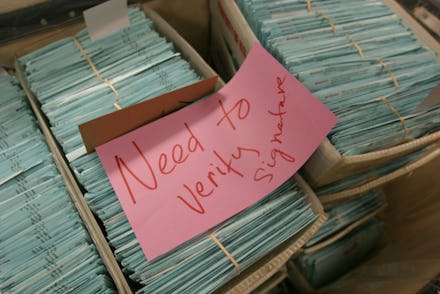

Republicans in the state argued that counting ballots that arrive after Nov. 3 presents a threat to election security, though Democrats and proponents of adjusting ballot rules and regulations say that there are a number of reasons voters should be allowed extra time for their ballots to arrive in the mail. Between the hamstrung Postal Service, which is struggling to deliver first-class mail — which includes ballots — on time, a pandemic-riddled election year, and the fact that local boards of election will likely be counting ballots for at least a couple days after Election Day anyway, proponents of ballot access say the Republican push isn't about election security so much as it is an attempt to suppress votes, as Democrats are more likely to vote by mail.

Each state is allowed to determine their own election laws, and that discrepancy has led to seemingly contradictory rulings from the Supreme Court. In September, the Pennsylvania Supreme Court ruled that ballots could arrive up to three days after Election Day and still be counted, a ruling that was challenged by Republicans in the state. A deadlocked Supreme Court earlier this month left the Pennsylvania court's ruling in place, with Chief Justice John Roberts joining the court's three liberals.

The justices acknowledged this contradiction in their opposite ruling on the Wisconsin case: "Different bodies of law and different precedents govern these two situations and require, in these particular circumstances, that we allow the modification of election rules in Pennsylvania but not Wisconsin," the denial to vacate the lower court ruling read.

This latest decision in Wisconsin caps off a contentious partisan fight over election law and ballot access in the state, and around the country. As Mark Joseph Stern wrote for Slate in August, just five months after the state's disastrous primary election, a June decision by a federal appeals court "upheld most of Republicans’ restrictions on ballot access, including a stringent voter ID requirement." Moreover, "anyone requesting an absentee ballot for the first time will have to provide a copy of an acceptable ID. (State or federal employee IDs don’t qualify, nor do out-of-state driver licenses.) And everyone who votes absentee must procure a 'witness' to watch them fill out the ballot, then sign the envelope." If that weren't enough, the court also upheld a Republican effort to cut the early in-person voting period from two to six weeks.

Elections are won and lost in Wisconsin by a handful of votes — in 2016, Democratic candidate Hillary Clinton lost by 23,000 votes, which happens to be the same number of ballots thrown out in this year's primary for not having a witness signature.

But possibly even more concerning is the implication this ruling by the Supreme Court has on the bench's view of the election's integrity. Justice Brett Kavanaugh wrote in his concurring opinion that absentee ballots arriving after Election Day would pave the way for increased voted fraud — nevermind that such fraud is in fact extremely rare. "Those states want to avoid the chaos and suspicions of impropriety that can ensue if thousands of absentee ballots flow in after election day and potentially flip the results of an election," Kavanaugh wrote, citing legal scholar and CNN contributor Rick Pildes.

But Kavanaugh's justification for restricting the ballot deadline miscited what Pildes actually recommended, which is that if officials don't expand the deadlines, then stakeholders are able to claim that the public can't trust the results of the election because so many people were disenfranchised.