Meet the Gay Activist Behind Martin Luther King Jr.'s Civil Rights Movement

Martin Luther King Jr. did not fight against racial discrimination alone.

While King is the face of the civil rights movement, he relied on a coalition of allies to make the movement possible, from ministers to activists, politicians to labor unions. So while there's no official document detailing King's support for the LGBT community, the fact that Bayard Rustin, one of his trusted advisers and strategists, was a black gay man speaks volumes about King's view on homosexuality.

"I appeal to everyone who believes in Martin Luther King's dream," King's widow, Coretta Scott King, said in a 1998 speech, "to make room at the table of brother and sisterhood for lesbian and gay people." While other leaders of '60s-era civil rights movement may have rejected homosexuality in their midst, King gave Rustin a seat at the table.

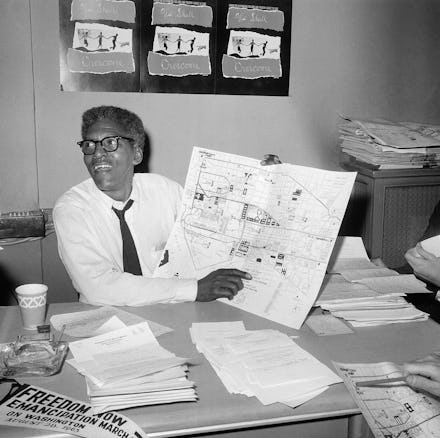

Born in 1912, Rustin was an early "freedom rider" in the 1940s and quickly rose to prominence in the burgeoning civil rights movement of the '50s and '60s. He is credited with organizing the Montgomery Bus Boycott in 1956 and the March on Washington in 1963, throughout which time he and King built a friendship.

In a 1987 essay published the year he died and recently reposted at the Advocate, Rustin elaborated upon how his homosexuality affected both their friendship and Rustin's place within the movement.

"It is difficult for me to know what Dr. King felt about gayness except to say that I'm sure he would have been sympathetic and would not have had the prejudicial view," wrote Rustin. "Otherwise he would not have hired me. He never felt it necessary to discuss that with me. He was under such extraordinary pressure about his own sex life. J. Edgar Hoover was spreading stories, and there were very real efforts to entrap him. I think at a given point he had to reach a decision. My being gay was not a problem for Dr. King but a problem for the movement."

In 1960, Rustin was forced to resign from the Southern Christian Leadership Conference, to which he and King were the two head organizers, because of threats from colleagues within the civil rights movement to both out Rustin and, as John D'Emilio contends in his Rustin biography, to spread rumors that Rustin and King were lovers.

Rustin was aware that the homophobic climate of America in the mid-20th century created tension in his friendship with King. In his essay, he writes, "It was never a prejudicial situation; it was that given the attitude at that time, people felt this was a problem."

But Rustin, who was posthumously awarded a Presidential Medal of Freedom in 2013, was a fighter, and continued his critical work behind closed doors but still standing alongside King in critical moments, most notably the March on Washington. It was Rustin's brilliant logistical and organizing skills that made the march happen. Some activists like the Rev. Irene Monroe, contend that it was through Rustin that King became the legend he is today, because the march "catapulted King onto the world stage."

Rustin's essay is a resounding moment that King stood for the dignity of all men, gay or straight. That other leaders within the movement disagreed with King and pressured him to fire Rustin because of his homosexuality is evidence that King was a leader ahead of his time.

After the successes of the Civil Rights Act of 1964 and the Voting Rights Act of 1965, Rustin turned his attention to gay rights, to which he dedicated the rest of his life. In 1986, one year prior to his death, he delivered the impassioned speech, "The New N****** Are Gays," as a way to create a dialogue between the black rights and gay rights movements.

"Blacks are no longer the litmus paper or the barometer of social change," he said. "Blacks are in every segment of society and there are laws that help to protect them from racial discrimination. The new 'n******' are gays. ... It is in this sense that gay people are the new barometer for social change."

Living as a gay black man throughout the 20th century, Rustin parlayed intersectional experience as both gay and black into his activism. He tried to make the civil rights movement less homophobic, and the gay rights movement less racist. At the same time, being the strategist that he was, he fully understood the political ties that bound people like King to restrain their activism, or to make more progressive elements of their political beliefs more covert and therefore more palatable to the general public.

Rustin knew King to be a good and honest man, who championed "radical love," "democratic socialism" and equality for all people. Whether King labeled himself a "gay ally" is not only an anachronistic dream, it's also not really important considering the archive of King's activism and his treatment of all people. In reality, it's Rustin's work both during the civil rights movement of King and throughout the last decades of his life that serves as a testament to King's vision for an equal nation.