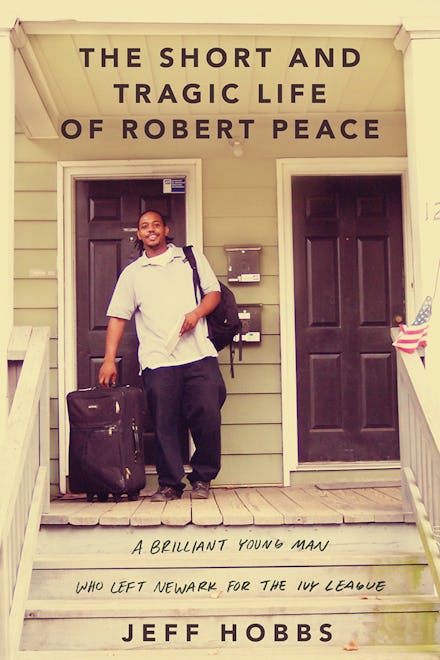

Mic Conversations: A Life Full of Potential Is Ultimately "Short and Tragic"

The "Pass the Mic" series showcases voices, perspectives and ideas that spark interesting conversations.

In his critically acclaimed New York Times bestseller The Short and Tragic Life of Robert Peace, Jeff Hobbs tells the story of a supremely intelligent man who earned a degree in molecular biochemistry and biophysics from Yale before returning to his hometown of Newark, New Jersey, after graduation. At the age of 30, Peace was murdered.

Hobbs and Peace were college roommates for four years, and Peace was a groomsman in Hobbs' wedding. Hobbs uses his unique vantage point, along with hundreds of hours of interviews with Peace's family, friends and acquaintances, to tell a gripping story of Peace's life, while exploring issues like race, privilege and loyalty.

Anand Giridharadas writes in his New York Times review that the story is "an interrogation of our national creed of self-invention. It reminds us that there are origins in this country of ours that cannot be escaped, traumas that have no balm, holes that Medicaid and charter schools and better mental health care and prison reform can never fill."

Mic spoke to Hobbs about the book, which was recently optioned for a film to be directed by Training Day's Antoine Fuqua.

Mic: When did you start to think about writing this book and then begin your effort in earnest?

Jeff Hobbs: His funeral was in May of 2011. In the months that followed, a community formed and not just mutual friends from Yale, but also from his hometown. A lot of conversations over the phone and in person. Teasing out the answers, we came up with very few answers but a lot more questions, and it was mainly just a reminder of how special Rob was and a collective movement to set down his narrative.

Mic: Can you speak to the process of getting to know all these people from his life and whether or not it was difficult to get their buy-in?

JH: I started, of course, with his mother, I sat with her in her home and said, 'You know we wanted to write a book about his life, not his death.' We felt that the sort of standard newspaper interpretation of a story of squandered potential didn't do justice to the actual human being, making decisions — not all of them wise decisions — but a lot of them very triumphant decisions, and she, courageously, really invested herself in this. And then I just kept reaching out to more and more people.

Mic: What was Robert like?

JH: One of the things that was easy for people to say or to think was that Robert was two people, that he lived in two worlds. And you know, I lived with the guy in close quarters for four years. I knew for a fact that he lived in one world. He traversed the contrasting areas pretty fluidly.

I met him at Yale, which was a foreign environment for him, different from almost every way from the environment he'd grown up in. But he attracted people to him. He was really funny, laughed a lot, didn't have a chip on his shoulder. He was a good dude, didn't complain a lot, but we also realized in retrospect that he didn't share a lot either, particularly when it came to anything that burdened him. His father was incarcerated for murder when Rob was 11 years old, but Rob kept a very close, deep relationship, even while his father was in prison.

Mic: How did the relationship with his father impact his life and the decisions he made?

JH: The real takeaway from his story is that life is messy, and for us to try to put decisions in boxes, you know, when you try to account for everything is impossible. Not being a psychologist or anything, I would say that losing his father to prison at a young age was a central moment and a central trauma in his life.

His parents weren't married but they were close in their relationship, and his father was a good father. He was very invested both in socializing Rob and sort of making him a man but also in academics and doing homework. When he was in jail, he continued to do homework with his son over the prison payphone. Unbeknownst to almost everybody in his orbit, [Rob] worked tirelessly to get his father out of prison, he firmly believed his father was innocent. He was never able to do that, and his father passed away in 2006.

Mic: And how about his mother? An incredible woman.

JH: If there's a perfect person in this story, it's Jackie Peace. I could go on and on about her, but a smart woman, a tough woman, a dignified woman and a loving woman. I would need another 400-page book to capture the scope of her loss. Rob was her only child.

"The real takeaway from his story is that life is messy, and for us to try to put decisions in boxes, you know, when you try to account for everything is impossible."

Mic: How did their relationship change over the course of his life?

That's an interesting question. As a kid who went through the loss of his father and also just adjusting in the environment that he was born into, Rob became an adult at a very young age and a partner to his mother as well as a son. He graduated Yale and his best friends were sort of telling him not to go back to Newark, you're better than where you came from, that sort of vibe, which he really didn't buy into at all.

He wanted to be with his mother and continue in that role as a sort of her rock. And I think that was really consistent throughout his life. I think something he could never swallow was that, you know, his mother had lived her life, lived it pretty well, best she could, raised an amazing son and maybe she didn't need him to be there in the way he wanted to.

Mic: What do you think he'd say about your book?

JH: I struggle with that throughout this, particularly since the publication, when you get a lot more exposure than certainly I anticipated. There are some details about his life that he probably wouldn't have enjoyed having shared. You know, we thought that if his story could spare another mother the grief that his [mother] experienced, then he would be all for that.

Mic: What do you think he'd be doing right now if he was still alive?

JH: What I hope is that he would be a teacher, probably in college, running his own lab and taking trips around the world, which was sort of his favorite thing to do possibly. He would be living very happily in Denver. He was a big fan of marijuana, for better or for worse, ultimately for worse. I like to think it would be some combination of that, the four things he loved: science, travel, weed and his mother.

"Rob had that quality in spades and was just so curious about people around him, no matter where they came from. He cared about sort of how you treated people, he cared about your character."

Mic: Did you ever struggle with any guilt about losing touch with him?

JH: Of course I did, and a lot of people did. He was hard to keep in touch with: His number was always changing and he was often out of the country. We were all sort of stumbling through our 20s and all the day-to-day tasks can obscure the really important things, like keeping in good touch with your friends.

Mic: The book has been optioned for a movie. Do you have concerns at all about maintaining the integrity of the story through the movie?

JH: I did. Primarily for his mother. I should say that her wishes for the proceeds both from the book and movie to fund a scholarship to St. Benedict, which was Rob's high school. I have spoken with the director Antoine Fuqua a couple times, and he's just really insightful and respectful of the story. He really seems to relate to Rob and his family, and so I'm not to concerned about him sort of taking the reigns off.

Mic: Is there a takeaway you want people to have after they have finish the book?

JH: For me the takeaway is just the value of empathy. Rob had that quality in spades and was just so curious about people around him, no matter where they came from. He cared about sort of how you treated people, he cared about your character.

We like to package things in boxes, and it's a lot harder to feel empathy for a story as troubling as this one, but I think we all could benefit [from empathy] when we read an article in the newspaper or see an interaction on the subway. People have lived lives and they are all stories, and when we're making policy and educating our kids, it seems like we should think about that.

This interview has been condensed and edited for clarity.