The Bizarre True Story of the Man Who Stole Einstein's Brain

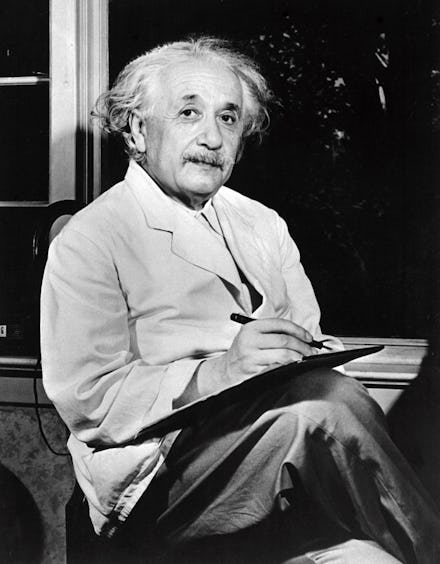

On April 18, 1955, Albert Einstein, one of the most brilliant scientists who ever lived, died of heart failure in a Princeton, New Jersey, hospital.

What happened right after that is pretty hard to believe.

Thomas Harvey, the pathologist on call that night, began Einstein's autopsy. As a pathologist, his only job was to determine the cause of death. Instead, without permission, Harvey cut out Einstein's brain, plunked it in a jar full of formalin, and took it to his home office.

Yeah, he stole Einstein's brain.

"Whether he took it for himself, or took it for science — it was hard for people to know which, and that's what put him in the crosshairs for a lot of people," said journalist Michael Paterniti.

It makes sense that the brain that dreamed up relativity, the concept of E = mc^2 and the photoelectric effect would be the subject of fascination. What made Einstein a genius? Was his brain superior to others?

But studying his brain went directly against Einstein's last wishes. According to Brian Burrell's book Postcards From the Brain Museum: The Improbable Search for Meaning in the Matter of Famous Minds, Einstein wanted his entire body cremated (including the brain) and his ashes scattered in secret to "discourage idolaters."

In other words, Einstein was smart enough to figure out that something like this might happen after his death, and he wanted to prevent it. Harvey did retroactively ask permission from Einstein's son, after he'd already removed the brain and stowed it away. Hans Einstein gave his blessing so long as real scientific studies were conducted and the results published in academic journals.

But what happened next was a bitter battle over who would get to study the brain first. Amid the controversy, Harvey was fired, but he took the brain with him. He traveled to the University of Pennsylvania, where he sliced up part of the brain into microscope slides and celluloid squares, and kept the rest in glass jars.

Then he and the brain left Princeton and ran off to the Midwest.

If Harvey had big plans to advance his career in medicine with the brain, it never happened. Instead, over the years, Harvey would occasionally send some slides of the brain to scientists who asked for them. Allegedly, during his time in Kansas, Harvey kept Einstein's brain in a cider box under a beer cooler.

Eventually, some scientific studies on Einstein's brain were published. Some claimed that his brain appeared to have more glial cells than the average brain, and that could lead to higher cognitive performance. But those studies have been largely discredited by modern science.

"You can't take just one brain of someone who is different from everyone else — and we pretty much all are — and say, 'Ah-ha! I have found the thing that makes T. Hines a stamp collector!'" Terence Hines, a psychologist and stamp collector, told the BBC.

Basically, we can't tell much of anything from one brain.

In the '90s, Harvey drove from Princeton to California to take the brain to Einstein's granddaughter. (You can read the whole story in the book Driving Mr. Albert). Einstein's granddaughter didn't want the brain, so when Harvey died in 2007, he donated it back to Princeton.

Where is it now? You can actually go see some pieces of the brain — it's at the Mütter Museum in Philadelphia.