Bill Bratton's Broken Policing Is Here to Stay

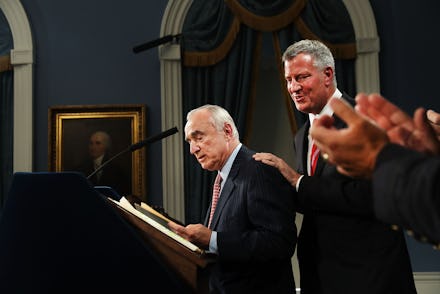

When New York City Mayor Bill de Blasio met reporters at City Hall to announce police commissioner Bill Bratton's retirement Tuesday, he stressed the department's shift toward what he called "neighborhood policing," a strategy that encourages officers to engage with people who live in the communities they're patrolling.

"We've tried to redefine our relationship from being the police to being your police," Bratton said.

But this approach is diametrically opposed to the controversial "broken windows" policy that Bratton championed during two stints as as head of New York's police force. During his campaign for mayor, de Blasio fervently opposed broken windows, which stringently enforces minor quality-of-life crimes in the hope of reducing more serious crime. But once in office, de Blasio caved to pressure from the New York Police Department and embraced the policy. Now, Bratton's successor will be tasked with implementing one strategy focused on the winning the community's trust and another that has slowly eroded it.

"Regardless of who is at the top of the NYPD, the problems remain systemic within the department and will not simply change with leadership, particularly if that leadership and the mayor remain committed to Bratton's discriminatory ideologies," Anthonine Pierre, a spokesperson for Communities United for Police Reform, said in a statement.

Broken Policing

Broken windows became popular in the 1980s as violent crime soared in America's cities. The New York Times described the "seemingly intractable spread of cocaine and its derivative, crack," which led murder in New York City to skyrocket from 1,683 in 1985 to 2,605 in 1990.

In an influential article in The Atlantic, social scientists James Q. Wilson of Harvard University and George L. Kelling of Northwestern University heralded a solution to the nation's crime wave. The answer was simple: Police weren't spending enough time enforcing small, quality-of-life crimes like littering, jumping over subway turnstiles and graffiti. Smaller crimes, they argued, lead to bigger ones. "We suggest that 'untended' behavior ... leads to the breakdown of community controls," they wrote. If police focused on combating minor infractions, it would cut down on serious crimes like rape and murder.

Bratton, then at the Boston Police Department, became one of the nation's leading proponents of broken windows policing. He decamped for New York City in 1990, becoming chief of the New York City Transit Police, before taking over the helm of the entire department in 1994. His first year in office, the department conducted 98,000 juvenile arrests — up from 20,000 the year before.

While Bratton and others touted the merits of broken windows policing, others argued that the policy unfairly targeted poor people and young people of color. Norman Siegel, then-executive director of the New York Civil Liberties Union, complained at the time that officers resorted to "questionable street-justice tactics" like illegal searches as a result of broken windows policing.

Bratton left the department in 1996, alternating between high-profile commissioner posts in Los Angeles and lucrative consulting gigs in Oakland, Calif. and London. He spread the gospel of broken windows far and wide, while New York City continued to implement it without him.

Indeed, the the crime wave that hit the country in the 1980s and early 1990s receded. From 1990 and 2014, crime fell 85%. Proponents of broken windows credited the policy with the drop, but critics have pointed out that crime fell nationwide over the last two decades — in cities that embraced broken windows as well as those that did not. The department's own inspector general, Philip Eure, analyzed data from 2010 to 2015 and found no evidence that enforcing quality-of-life crimes "has any impact in reducing violent crime."

Stop and Frisk

In 2002, the New York City Police Department took broken windows policing further. Under a controversial program called "stop and frisk," officers stopped pedestrians, questioned them, then search them for weapons or drugs. At its peak in 2011, stop and frisks resulted in 2.6 million law enforcement interactions; police found illegal guns 0.1% of the time.

The program drew criticism from communities of color, who said stop and frisk disproportionately targeted minorities and fomented distrust between police and the communities they monitored. One in five people stopped by the NYPD in 2011 were teenagers between the ages of 14 and 18, and 86 percent of those teens were black or Latino, according to data analyzed by WNYC. In 2013, the a federal court ruled the NYPD's stop-and-frisk program unconstitutional, finding that the practice violated residents' Fourth Amendment right to be free of unreasonable searches and seizures.

De Blasio Backtracks

Bill de Blasio was swept into New York City's mayor's office in 2014 riding a wave of populist support. An important part of his platform was his opposition to broken windows policing, exemplified by the NYPD's stop and frisk program. At one point during the campaign, de Blasio enlisted his biracial teenage son, Dante in a campaign ad. "He's the only one who will end a stop-and-frisk era that unfairly targets people of color," Dante said of his father.

But once in office, de Blasio wasn't only accountable to the voters of color who supported his election, but to the police department. To help bolster his crime-fighting credentials, he brought Bratton back as head of the NYPD. He changed his tune on broken windows. In a 2015 speech, de Blasio said the policy "has been a crucial element in reducing crime."

With crime falling historic lows, the public began to demand an end to tough-on-crime policies from the 1980s and 1990s. Under the banner of "Black Lives Matter," protesters in cities across the country have called for an end to indiscriminate use of police force. That debate hit home in New York City in July 2014, when police confronted 43-year-old black man Eric Garner outside of a convenience store for selling cigarettes — exactly the type of low-level offense that, according to Wilson and Kelling's broken windows theory, led to violent crime. Officers swarmed the scene, tackling Garner to the ground and putting him in a chokehold despite his repeated pleas of "I can't breathe!" He died as a result of the altercation. For many, Garner's death exemplified the problem with broken windows.

In the aftermath of Garner's death, de Blasio has promoted "community policing" as an alternative to stop-and-frisk. In total, de Blasio, Bratton, and Bratton's soon-to-be successor, a 30-year-veteran named James O'Neill, said the phrase "neighborhood policing" 21 times at Tuesday's press conference.

"I think that neighborhood policing — again, it's a strategy we have never fully achieved, and it will change everything because it changes the relationship between the community and the police fundamentally," the mayor said. "But I very much believe in quality of life enforcement."

The mixed approach will test soon-to-be Commissioner O'Neill's ability to placate frustrated communities of color and the police. But it's that daunting task is made even harder by trying to implement two such diametrically opposed strategies in a department that is always in the hot seat.