Police shooting investigations are rarely transparent. Just ask these victims' families.

Constance Malcolm is fed up. It's been just over five years since former New York City police officer Richard Haste stormed into her Bronx home and opened fire on her unarmed son, 18-year-old Ramarley Graham.

Two state prosecutions, a federal criminal civil rights investigation and an internal NYPD trial have yet to yield any measure of accountability for Haste and other officers involved in Graham's 2012 shooting death. Nothing about the last five years has been transparent, and the city's mayor and police commissioner have been complicit in keeping her in the dark, Malcolm has said.

"How can I move forward and heal?" she asked Monday during a news conference outside of police headquarters in Manhattan, after officials announced Haste's sudden resignation. The officer was allowed to resign after an internal NYPD disciplinary trial found he had exercised poor judgment and acted in a way that showed he meant to harm Malcolm's son.

"There's no room for [healing] because I still have no answers," Graham's mother said, choking back tears. "But I guarantee, I will never give up."

For Malcolm, the latest developments in her son's case are only made worse by the slow trickle of information that she has received about the officers involved in his death. Haste's previously secret record with the New York City Civilian Complaint Review Board shows he had six complaints lodged against him before he killed Graham. He'd allegedly used physical force, pepper spray, offensive language and abusive frisk tactics against civilians, according to documents published Tuesday on the website ThinkProgress.

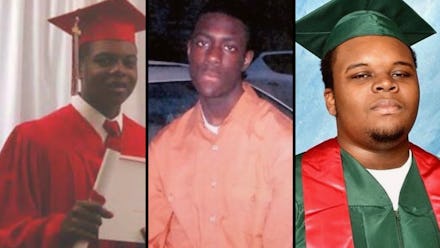

This is clearly a trend for police-involved incidents. Years after their deaths at the hands of officers, the families of Graham, Laquan McDonald and Mike Brown, among others, are still learning the full extent of the officers' backgrounds and the circumstances around what happened the day their loved ones were killed. Haphazard releases of disciplinary records or previously sealed court documents have ripped open old wounds.

"Accountability and transparency shouldn't be based on what's convenient for Mayor [Bill] de Blasio, it should be based on truth and justice without delays," Malcolm said in a statement after civilian complaints appeared in media reports.

For many, the lack of transparency not only delays justice for all involved but also sends a message to families and communities that their deaths aren't matters that require urgent resolution. And when investigations are botched or are shrouded in secrecy, the affected families and communities are left with the impression that, as is true of transparency, justice after a police-involved death is rare, too.

"This is how it's been since the beginning," Loyda Colon, co-director of the Justice Committee, a member of the collective Communities United for Police Reform, said in a phone interview. "It not only takes some families anywhere from 5 to 10 years to get some answers. The reality is most families don't get any answers."

Colon, who has worked with families impacted by police violence since the mid-1980s, said Graham's family has experienced extraordinary levels of failure at every level of government.

"What that family has been through is outrageous," Colon said.

On Feb. 2, 2012, Haste and other NYPD officers chased Graham into his Bronx home, believing that he was armed. Haste shot and killed Graham near a bathroom in the home, as Graham's family members watched. Graham did not have a weapon.

Over the last five years, Haste has been indicted for manslaughter — but the case was thrown out of court due to prosecutorial error, and a grand jury declined to indict him a second time. The U.S. Attorney's Office in Manhattan investigated the case and also declined to press criminal civil rights charges against Haste. On March 24, an NYPD trial commissioner found Haste guilty on internal departmental charges that he "exercised poor tactical judgment leading up to the discharge of his firearm" and "acted with intent to cause serious physical injury leading to the death" of Graham.

Haste's ability to resign without official reprimand left the Graham family incensed and drew sharp criticism from national civil rights leaders.

"We share the Graham family's palpable disappointment with the NYPD's unwillingness to fire Richard Haste," Sherrilyn Ifill, president and director-counsel of the NAACP Legal Defense and Education Fund, said in a statement released Wednesday.

"The life of a young man has been cut short at the hands of police, and not a single officer has been held accountable," Ifill said. "We therefore urge NYPD officials to pursue disciplinary action against the other officers involved in Mr. Graham's death, including Sgt. Scott Morris and Officer John McLoughlin."

The lack of transparency — and in some cases actual police coverups — amid investigations has been seen in a number of other high-profile cases in the U.S. In Chicago, it took a full year of public pressure for the October 2014 police shooting death of 17-year-old Laquan McDonald to be revealed as a clear use of excessive force. Officers apparently made false statements about McDonald's demeanor and movements during an encounter with Officer Jason Van Dyke, who shot the unarmed teen 16 times and was charged in criminal court in 2015. These charges were only filed after previously sealed police dashboard camera footage showed McDonald did not lunge at officers before Van Dyke opened fire, as the officers had claimed.

"There's a reason why they don't want us to see [the video,] and don't want [it] to be made public," Johnae Strong, a Chicago organizer with the Black Youth Project 100, a group affiliated with the Black Lives Matter movement. "We know how the police are protected. We know that the city would just really love to pay [the families] off."

"So, it does make it very difficult when you know you are working in that system," Strong added.

On March 23, a grand jury added 16 counts of aggravated battery with a firearm to Van Dyke's first-degree murder case. These charges were made more than two years after the initial incident.

Mike Brown's police shooting death in Ferguson, Missouri, is perhaps the most recognizable case of police-involved death of the last decade. The August 2014 shooting sparked massive protests from BLM activists, but former Ferguson policeman Darren Wilson, the officer who shot 18-year-old Brown, was not indicted on state or federal charges.

On March 14, the Washington Post reported on court documents showing Wilson admitted to using the word "nigger" while on-duty. The documents stem from a civil suit filed by Brown's family. While Wilson's admission does nothing to change possibility of criminal charges, it's information about Wilson that wasn't available to the public as a grand jury decided his fate. It shows just how insulated officers are from public scrutiny about their background.

Peter Moskos, a professor in John Jay College's Department of Law & Police Science and Criminal Justice Administration in New York City, said the response and level of transparency by a department after a shooting often depends on the size of the department. "I never underestimate the sheer incompetence" of some police departments, Moskos said in a phone interview.

"The natural instinct is to not reveal information, and that's not a bad thing," Moskos said in reference to the law enforcement need of maintaining the integrity of an investigation. "But it has to be weighed with the public interest."

State laws and police union contracts also dictate what information officials are allowed to release to the public, including information pertaining to a police officer's past. Following the 2014 chokehold death of Eric Garner by plainclothes police Officer Daniel Pantaleo in Staten Island, New York, the public was not allowed to learn what information the local prosecutor presented to grand jurors, who declined to indict him. A state law prevents disclosure of grand jury proceedings.

The same happened in Graham's case, Colon, the New York City police reform activist, said, noting "We'll never really know what the [district attorney's] office actually presented to the grand jury because it's illegal for us to look at grand jury transcripts."

That has never been acceptable for Malcolm, Graham's mom. In 2015, she successfully fought for an executive order that would allow the New York state attorney general to investigate police-involved death cases. She said city leaders need to get more serious about transparency.

"Through their actions, it seems that the Mayor and Commissioner are more concerned with how they look in the media, instead of directly dealing with the concerns I have as a mother whose son was killed by their NYPD over five years ago," Malcolm said in a statement released Wednesday.

"This isn't just about tragedy, it's about the truth and police misconduct that de Blasio seems to have no interest in pursuing," she said.