The Collateral Catastrophe: Serving the Invisible Life Sentence

Five Mualimm-ak, 38, spent 12 years in prison for alleged assault on police officers, trafficking and drug possession. He was released in January 2012 and was homeless until a couple of months ago. Because of his criminal record, he could not get a job, live in public housing or get food stamps.

His story is emblematic of a bigger national problem: Some of the people most desperately in need of this assistance are also the people completely deprived of it. The news site Colorlines reported Thursday that 10 states ban people with felony drug convictions from receiving food stamps.

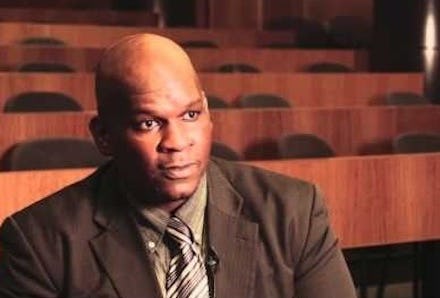

Daniel Luke, 44, has found himself in a similar position after getting charged with burglary (he'd broken into his ex's house in a rage) in December 2010. He was released two years later. When asked about the collateral damage his conviction caused himself and his family, he said, "[I'm] homeless. Haven't seen my kids in three years. I get work cleaning houses by posting to Craigslist."

If a person has a felony record, serving the prison sentence does not just mean lost years. It entails missed opportunities to gain useful skills, earn a living wage and forge a meaningful and supportive network. The prison sentence might be over, but the life sentence — the relegation to second-class citizenship — is just beginning.

The American Bar Association (ABA) identified 11 categories in which a felon experiences collateral consequences of his or her conviction:

1. Government loans and grants

I recently interviewed Bernard Kerik, former NYPD police commissioner who was sentenced to four years in federal prison for tax fraud and false statements. Today, he is a convicted felon. Kerik estimated, "There are probably 50,000 collateral consequences of your felony."

He wasn't far off. The Huffington Post reported recently that the ABA identified "38,000 collateral sanctions that people involved in various ways with the criminal legal system face on top of their court mandated sentences." The sanctions extend "to nearly every facet of daily life." Kerik noted that even working as a garbageman or as a barber post-release can be off limits, as they require state licensing.

In 2013, President Barack Obama and the Department of Justice announced that for federal drug offenses, judges will now decide whether to apply the mandatory minimum sentence to convicts, provided the defendant is nonviolent and not connected to a drug cartel or gang. This modification is also a top priority for Attorney General Eric Holder, who published the "Smart on Crime" initiative in August 2013. The initiative has five major goals: ensure finite resources are devoted to the most important law enforcement priorities; promote fairer enforcement of the laws and alleviate disparate impacts of the criminal justice system; ensure just punishments for low-level, nonviolent convictions; bolster prevention and reentry efforts to deter crime and reduce recidivism; and strengthen protections for vulnerable populations.

The initiative is a step in the right direction. But it's missing something: Simply reducing the length of a person's sentence, for example, doesn't change the label permanently stamped on his or her record. It doesn't change the fact that that person will be significantly restricted in nearly every way.

A plan to reduce unjust collateral damage is sorely missing from the initiative's priorities. Holder himself has even admitted that many of these civil penalties "serve no public safety purpose at all" and that "many actually create the conditions that are most prevalently associated with crime, such as joblessness," as Huffington Post wrote. But where is the action? He was waiting on the analysis from the ABA to determine if collateral consequences are "unduly burdensome." Well, they've been found to be unduly burdensome.

While it's encouraging that the issue has come to our leading politicians' attention, there is a disconcerting lack of urgency on the matter. We deprive our ex-offenders of basic means for survival, which fuels recidivism. Our country's rate of recidivism (return to prison) is "unacceptably high," to use Holder's words, and thereby poses a greater risk and cost to society.

If we're going to claim that America has "enduring values" of "equality, opportunity and justice under law," then we simply have to do better.

(Image credit: Daniel Luke, Five Mualimm-ak and the Associated Press)