What the U.S. Can Learn From the Rest of the World About How to Treat Fathers

This Father's Day, let's forget the beer and golf balls and give dads what they really need: paid paternity leave.

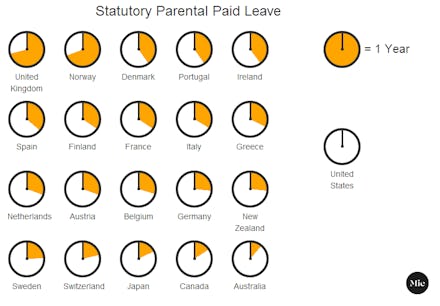

Given that the U.S. is the only high-income country in the world without statutory paid maternity leave,* paid paternity leave might feel like wishful thinking. It shouldn't. Parental leave is not simply a luxury, for mothers or for fathers; it's a necessity. And while enshrining statutory maternity pay may be a more popular topic for debate on the cable news networks, paternity leave musn't be ignored, either. At its heart, this is a feminist issue, too.

The U.S. remains dismally behind the rest of the world when it comes to leave for either parent, despite the fact that studies show paid leave in particular is hugely important to the well-being of new families. According to the National Compensation Survey, just 12% of employees have access to paid leave for care of family members. This means that those workers with the lowest incomes also have the least access to paid leave, for either parent. As a result, new babies push many families into deep debt.

The federal Family and Medical Leave Act of 1993 (FMLA) grants eligible employees up to 12 weeks of unpaid leave for the care of a child (or any family member), but this doesn't go nearly far enough: About 41% of workers are not covered under FMLA, and many of those who are simply can't afford to take leave without pay.

New fathers take far less time off than new mothers, but this isn't an issue of varying levels of devotion. The fifth annual study on working dads from Boston College's Center for Work & Family (CWF) found, perhaps unsurprisingly, that fathers take about as much leave as they're offered. But although more employers are beginning to grant parental leave, this often comes in the form of a shared entitlement that either parent can take up — something men rarely do, especially when it's unpaid. And it nearly always is.

In the fight for true gender equality, paternity leave might be one of the most surprisingly effective tools in our arsenal.

Eight-six percent of CWF's respondents asserted they wouldn't take leave at less than 70% of their salary, a rarity outside of progressive Silicon Valley companies (Facebook, for example, now generously offers new dads four months paid time off). This is obviously in large part because most families simply can't afford the paycheck hit. But more subtly, as men continue to be gender stereotyped as providers rather than caretakers, taking an unpaid or extended paternity leave can carry a social stigma that professional men may seek to avoid.

This past April, for example, Mets second baseman Daniel Murphy made headlines for taking Major League Baseball up on its three-day paternity leave policy. Though league officials supported Murphy, sports commentators weren't so kind. Multiple radio hosts publicly slammed Murphy's decision to miss an astounding two games to witness the birth of his son. "What are you going to do?" one of the hosts asked on the air. "I mean you are going to sit there and look at your wife in a hospital bed for two days?"

Ignorant sports commenters aside, there's actually a lot that new fathers can, and should, do. Luckily for them and their families, it seems that cultural attitudes are shifting to be more accepting, even encouraging, of paternal leave, especially in younger industries like tech. This is important, and not just for dads who no longer have to miss out on invaluable bonding time with their kids: The benefits of paid paternity leave extend well beyond fathers to encompass moms, children and even employers.

On the most immediate level, paid leave allows fathers to fully support mothers who have just gone through a physical trauma (whether this is giving birth or having a c-section, a major surgery). Such support becomes all the more important if a woman has any health complications, including postpartum depression. Dads also can join in the emotional bonding that comes with welcoming a new child, whether biological or adopted, and complete a fairer share of basic childcare and domestic duties during an extremely influential period in a child, and couple's, life.

More broadly, taking leave, especially two weeks or more following childbirth, can set the stage for increased paternal involvement and uptake of family responsibilities in the future. The habits established now influence later parenting dynamics, and more involvement may lead to more equitable relationships. According to an International Labour Organization policy brief on the subject, early, adequate leave "can have positive effects for gender equality in the home and at work and may indicate shifts in relationships and perceptions of parenting roles and prevailing stereotypes."

Writing in the Atlantic, Liza Mundy goes so far as to call paternity leave "a brilliant and ambitious form of social engineering: a behavior-modification tool that has been shown to boost male participation in the household, enhance female participation in the labor force, and promote gender equity in both domains."

She's right. In the fight for true gender equality, paternity leave might be one of the most surprisingly effective tools in our arsenal. Encouraging dads to lean out, in a sense, is a simple way to lessen the burden of the "second shift" of domestic duties that many women still face after a long work day, despite increasingly taking on the role of the family's primary breadwinner. And allowing women to thrive is undeniably a good thing. As Mundy notes, the World Economic Forum's latest global gender gap report revealed that "countries with the strongest economies are those that have found ways to further women's careers, close the gender pay gap, and keep women — who in most nations are now better educated than men — tethered to the workforce after they become mothers."

For new dads, it's not enough to offer the option of parental leave — to really spur change, it should be actively de-stigmatized for fathers, and at least partially paid. Countries like Norway, Iceland, Germany and Finland are leading the charge on this front, by incentivising paternal leave with pay or by allotting a certain number of days solely to dads.

The U.S. desperately needs to catch up. We need to show that it's not just acceptable but expected for men to partake in domestic duties. Because this isn't about lauding fathers for doing the same work that moms have always done. It's about recognizing that paternity leave is good for everyone.

Image Credit: Uproxx

*Based on 185 countries and territories with information available for study.