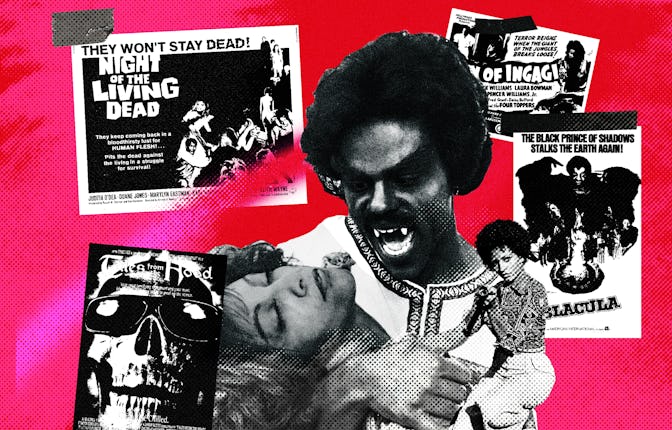

Black Horror 101

A look at the long list of creators and actors of color who paved the way for Jordan Peele’s Nope.

The first big blockbuster film in the United States that depicted the concept of Black people as the other — something to be feared — was Birth of a Nation. It was a 1915 propaganda film, rooted in the idea that Black men were unintelligent monsters whose insatiable lust for white women was a danger to society. The only way to deal with these so-called creatures — who in the film were played by white men in blackface — was to kill them. The film, which premiered at Woodrow Wilson’s White House, glorified the Ku Klux Klan and lynching and stoked racial tension and stereotypes.

Thankfully, society has progressed somewhat, but that concept of othering has followed Black people and people of color in film for decades. Even when there’s a slasher film that has no real plot beyond gore, it’s hard not to root for everybody Black — the others — primarily due to the belief that Black people always die first. It’s a faulty stereotype, but there’s truth in it: Black stories, characters, and storylines are more likely to be sidelined or forgotten because they are the other. From the perspective of a group that is always centered as the main narrative, that concept is hard to relate to.

Jordan Peele’s Nope, however, uses the concept of the others as the main characters. It centers around people of color, from oft marginalized groups, as they deal with actual others, aliens. But to understand how the concept of othering has surfaced throughout the Black Horror genre, you have to look at movies that centered Black characters and Black stories in the context of Black Horror Movie History. Here are ten landmark moments and concepts from horror movies that highlighted Black talent in ways that pushed the genre forward.

Son of Ingagi - First Black Woman in STEM

Son of Ingagi was Spencer Williams’ answer to the stereotypical images of Black people — which were largely played by white people in blackface at that time — that had been depicted in the media. Williams, who starred in Amos and Andy, wrote the 1940 screenplay about a Black woman scientist helping a half-man/half-ape creature. This film was groundbreaking because at the time, women — especially Black women — were not featured as doctors or anything remotely close on screen. The overall story arc featured Black characters who were depicted as smart and productive adults instead of the cliche stereotypes at that time, which were lazy, lusty, mischievous, and childlike.

Night of the Living Dead’s Ben as The Hero

George A. Romero made a brazen move by casting Duane Jones as a leading man in his 1968 classic, Night of the Living Dead. Jones, a Black man, ends up being the hero. Ben, who is hiding from zombies in an abandoned home, takes in Barbara, a terrified and traumatized white woman who finds the home in her quest to survive, but you can’t shake the feeling that she’s forced to trust this strange Black man given the circumstances. Other people find the home throughout the movie, and Ben keeps them all alive. He’s a standup character and a straight shooter who always seems to have a plan and calls people out on the foolish behavior that can get them killed. He’s a badass, but still meets a tragic death at the end when the cavalry arrives: a group of white men who stand outside the house and plan to shoot every zombie they see. When Ben goes near the window to survey the scene, one of the men hastily shoots him in the head, mistaking him for a zombie. It’s a horrific ending with heavy undertones: Ben survived zombies but not the mob of white men with guns.

Tales From the Hood’s many messages

The title of this 1995 film references Tales From The Crypt, a beloved horror-themed TV show from the same decade, but with an urban spin. It came out during a time when movies like Juice and Boyz in the Hood, which told stories about young adults navigating life and making life-or-death decisions in rough inner-city neighborhoods, dominated big screens. The messages in this movie were conveyed via a series of vignettes that covered ghastly topics with a focus on Black trauma, including police brutality, gang violence, domestic violence, racist politicians, and Black magic folklore, with each story threaded into a larger narrative. The film starts with three gangsters buying drugs from an eccentric funeral home director, portrayed by Clarence Williams III. He lures the trio inside and begins to share tales — a Black politician who is murdered by police; a little boy terrorized by a monster that is a metaphor for his mother’s abusive boyfriend; an incarcerated criminal who is forced to look at the impact of his violence; and a racist politician who gets his karma by way of dolls possessed by the souls of slaves. By the time the gang members hear each story, it’s clear that everything went over their heads. They don’t think any of that trauma and oppression have anything to do with them, but in the grand scheme of things, the point is that if Black people don’t work together, we’re doomed to repeat cycles. The three gang members don’t get to learn that lesson, though: the film ends with the funeral director revealing himself as Satan. They unknowingly entered hell after being murdered in a retaliation shooting, more victims of gang violence.

Lovecraft Country’s Topsy and Bopsy episode

Each episode of Lovecraft Country is crafted to convey that the characters are facing two monsters: the real-life racial violence of the 50s and actual supernatural beings and events. Episode 8 is an especially disturbing commentary about the need to protect Black women and girls. In this case, a teenager named Diana, who was the main character Atticus’ (Jonathan Majors) cousin, was overcome with grief after the murder of her friend, Emmett Till. Her family doesn’t notice when she somberly departs his funeral alone, leaving her to get cursed by a white police officer. The curse causes Topsy and Bopsy, a pair of demonic pickaninnies, to chase her throughout the streets of Chicago. The pickaninny is already an image that conjures fear in the minds of Black people. Pickaninnies embody the stereotype of what Black children look like to white people: little monsters. In Lovecraft Country, Topsy and Bopsy chase Diana with sinister smiles while gnashing jagged teeth and swiping their talons at her as she tries to escape. She’s the only one who can see them and the only one fighting them for an entire day until the adults who should be comforting and protecting her realize that she’s in trouble when it’s almost too late.

Scream Blacula Scream on voodoo

Blacula’s story begins with the first installment released in 1972. That movie opens with an African Prince named Mamuwaldi who, for an odd reason that’s never explained, heads to Transylvania to seek Dracula’s help with eradicating the slave trade. That obviously doesn’t go well. It results in Dracula cursing Mamuwaldi by turning him into a vampire and dubbing him “Blacula.” The concept of a “Black Dracula” hadn’t been done before, but let’s fast forward to the 1973 sequel, Scream Blacula Scream. In this follow-up, Pam Grier plays Lisa, a historian of African spirituality and high priestess of voodoo. Blacula recognizes Lisa’s power and asks her to help him break his curse. This is one film of that era where Grier gets to show more acting range. It’s also important to note that they’re not in Louisiana, which seems to be Hollywood’s oft-favorite and cliche setting for voodoo practice, and that voodoo is seen as a force of good, for the most part. That’s not to say the depictions of voodoo here aren’t ridiculous at times — it is a movie from the ’70s, after all — but it was a change from the standard then.

Vampires Vs. The Bronx - growing up marginalized in New York

On the surface, Vampires Vs. The Bronx is about a group of teenagers who save their neighborhood from vampires. But there are layers to it. The people, who turn out to be vampires in the end, are part of a wave of new implants in the neighborhood. The flood of new residents is accompanied by changes: many of the mom-and-pop shops are being bought out or have to close, because they can’t make the rising rents. In other words, the vampires moving in are a metaphor for gentrification. The heroic teens are the perfect representation of the types of everyday New York City kids who avoid criminal activity and rarely get media recognition for their good deeds. They come from a variety of backgrounds including Afro-Latino, African-American, and Caribbean-American — which accurately reflects the types of blackness one would encounter in New York. This is a campy movie that in spite of being a horror film, has hilarious moments, like when one of the protagonists successfully uses Adobo as a weapon against the vampires and makes brilliant commentary on what gentrification can feel like to locals: like the life being sucked out, pun intended.

The Space Traders - respectability won’t save you

The premise of this Reginald Hudlin-directed short, based on a short story by Derrick Bell, is that aliens come to Earth and ask for all of its inhabitants who contain 2500 milligrams of melanin in their skin per square centimeter. Basically, they’re looking for dark-skinned Black people. The trade-off is that the aliens would give them limitless resources including precious metals, cheap and sustainable energy, and replenish the Earth’s environment — you know, restoring all the good stuff humans destroyed. The aliens won’t tell them what would happen to Black people once they get a hold of them, but the tragedy is that the top politicians and non-Black citizens, who have five days to make a decision, want to make the trade anyway by a whopping 63 percent margin. The aliens tell them they won’t be coerced either, so they could just say no, but the deal sounds too good. This poses a problem for Professor Gleason Golightly, a prominent Black conservative who participates in the president’s discussion of the trade. Golightly is usually along the lines of Clarence Thomas when it comes to racial matters, but he is adamantly against the trade at first for moral reasons, but also because his light-skinned wife wouldn’t make the cut. In the end, Golightly's illusion of privilege does not save him. He tries to sneak away with his family, but the national guard, who sets up collection centers to round up the Black folk, forces him, his son, and daughter, along with all the other melanated people onto the spaceships at gunpoint. Viewers are intentionally left hanging about their fate, which could obviously go a million ways but ultimately, America let the Black people down. Ironic.

Tales From The Crypt: Demon Knight - the Black “final girl”

The “final girl” trope, which was coined by Carol J. Clover, author of Men, Women, and Chainsaws: Gender in the Modern Horror Film, is common in horror. In short, it’s the woman who survives everything but it’s not that simple. The final girl exists in the context of a patriarchal system that says independent women must be destroyed. Stereotypical final girls are usually white, and virginal, and avoid unladylike vices. Final girls, from a patriarchal lens, must be worthy of being saved. But when she saves herself and/or others, she defies that system of oppression, whether she is “pure” or not. Clover asserts that Lila Crane from Psycho (1960) is the first final girl ever. Pam Grier, Marki Bey, Vonetta McGee, and Janee Michelle, are among the first Black final girls in the 70s, but in the context of horror history, Black women had stopped being prominently featured in films in the 1980s.

Therefore, Jada Pinkett Smith’s appearance in 1995’s Tales From the Crypt: Demon Knight kicked off a resurgence of tough Black women on screen and definitely Black final girls. Demon Knight was a different type of role for Pinkett, who had previously done A Different World, Jason’s Lyric, Menace II Society, and The Inkwell. In this movie, which was presented by the HBO TV series Tales From the Crypt, Pinkett Smith plays Jeryline, a convicted thief on a work order release — the type of character that’s usually expendable or charity in movies. However, Jeryline surpasses expectations after crossing paths with a man known as Brayker, who is in pursuit of “The Collector.” The Collector is a demon in human form who is on a quest to unleash evil forces upon the universe by collecting the last of seven keys that will spark chaos. In the end, Jerilyn becomes the last person standing, defeats The Collector, and saves the world. The movie ends with Jerilyn on a bus headed out of town. It stops to pick up a man whose presence gets Jerilyn’s Spidey Senses tingling. He doesn’t get on the bus because he can’t, since Jerilyn holds the key that contains the blood of the previous keeper as protection. He tells the bus driver that he’ll catch the next one but exchanges a knowing glance with Jerilyn, as the bus pulls away, and begins to follow it on foot. Jerilyn understands that she is the new keeper of the key, who will continue the fight to save the world until it’s her turn to anoint a new warrior.

What follows after Demon Knight, up to the present day, is a slew of movies where Black women end up saving the world. Honorable Black final girl mentions include Brandy in I Know What You Did Last Summer, Sennia Nanua in The Girl With All the Gifts, and Sanaa Lathan in Alien Vs. Predator, Naomie Harris in 28 Days Later, Adina Porter in American Horror Story: Cult, Lupita Nyong’o in US, and more.

Candyman - Entrenched in a True American Horror Story

The original Candyman is a classic. Even people who haven’t seen the movie, but remember being a kid in the 90s, probably remember the urban legend that said that if you repeated his name five times in the mirror, in the dark for extra drama, then he’d appear and gut you like a fish. That was his MO in the movie. The character Grandville T. Candyman was a famed portrait painter from a prominent Black family in 1870s Chicago who was commissioned to paint Helen, the daughter of a wealthy white landowner. Candyman (originally portrayed by Tony Todd) and Helen fell in love, a forbidden affair that summoned the wrath of a white lynch mob. The mob cut off his painting hand and covered him with honey, cheering as he was stung to death by bees. Fast-forward to present-day Chicago and you have Candyman, a vengeful demon who stalks the residents of Cabrini-Green, a low-income housing project inhabited predominately by Black people. Even back then, there were some things that didn’t make sense. Why would Candyman terrorize his own people, who are already traumatized by the hardships of life, when the likely descendants of the people who murdered him were living in swanky high rises right across the tracks? It also may not have been the best choice to feed into the Black man lusting after a white woman stereotype. However, Candyman was initially written by a white man with a white man in mind to play the lead role. There is a story about that that is worth looking into.

Get Out sparked a horror movie renaissance

Jordan Peele’s Get Out sparked a renewed interest in horror films that centered on Black characters and stories. Many filmmakers who were inspired by him attempted to do what Peele did with Get Out but not quite on the same level. The brilliance of Get Out is that a lot of the violence you saw was psychological. It leaned heavily into microaggressions and things you might not notice overtly upon first watch. It began with Lakeith Stanfield’s character walking alone through the suburbs at night. The character commented about being freaked out while being the only Black man walking through the suburbs, knowing the risk that poses — and his suspicions ended up being true. Eventually, we get to the main storyline starring Chris (Daniel Kaluuya), a Black man who visits his white girlfriend’s parents for the weekend. His uneasiness around them proves to be valid once he learns that they are literally trying to snatch his body. More specifically, his girlfriend's family has made a business out of luring strong and beautiful Black specimens to their town with the intention of taking over their minds and bodies, leaving Black consciousness as a passenger in the terrifying “sunken place.” This film could have ended really badly for Chris, but thankfully, he made it out alive. Jordan Peele was intentional about making sure it had a happy ending.