‘The Murder Inc Story’ shows the best and worst of Irv Gotti

The BET docuseries further legitimizes the producer/exec’s legendary run, but comes short of the redemption arc that he’d hope for.

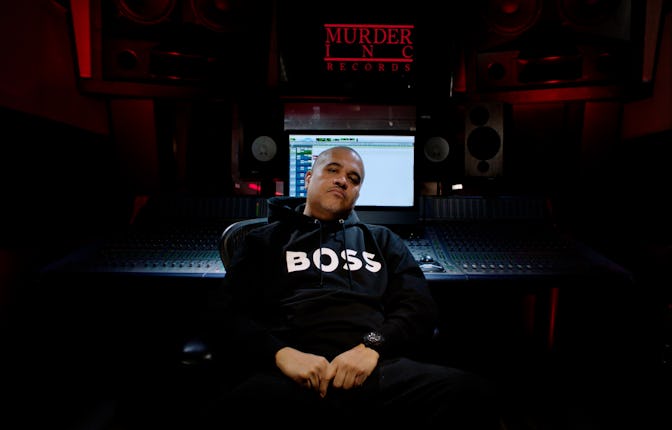

BET’s five-part docuseries The Murder Inc Story is meant to remind people that before 50 Cent and the federal government each tried to play spoiler to Murder Inc Records, Irv Gotti’s label made one of the most historic runs ever in pop culture. The gist is that decades later, the label — and its leader — deserve redemption. “Nobody beats the Feds,” Gotti said in an interview promoting the docuseries. “I was supposed to be gone. I’m not supposed to be sitting in this big ass house, chilling and making movies. And that’s why the timing of the story is great.”

Gotti is correct that it’s a great time for The Murder Inc. Story to come out. The docuseries examines his journey from music executive at Def Jam to becoming the mastermind of his own label that sold over 30 million records and grossed over $500 million worldwide — all in a relatively short time. DJ Irv, as he was known then, started his career in the music industry by producing rapper Mic Geronimo’s debut album, The Natural. Gotti went on to work with Jay-Z, producing “Can I Live” on the rapper’s debut Reasonable Doubt; and he was instrumental in getting DMX signed to Def Jam, in addition to producing on X’s monumental 1998 albums It’s Dark and Hell Is Hot and Flesh of My Flesh, Blood of My Blood.

Gotta could have had lifetime bragging rights on those merits alone. Instead, he launched Murder Inc Records, with Ja Rule as his flagship artist and vice president of the imprint. The label catapulted the careers of Rule and a slew of artists: Ashanti, Lloyd, Charli Baltimore, Vita, Black Child, and Caddillac Tah, and The Murder Inc Story captures the Inc’s ups and downs during that period. The docuseries successfully reminds viewers just how impactful the label was and cements Gotti as a visionary.

Unfortunately, Gotti distracted from the redemption arc with the spectacle he created after revealing in an interview with Drink Champs that he and Ashanti were in a relationship “every day for like two years.” While promoting the doc, he’s talked nonstop about how the pair mixed business and personal. Gotti, who has since branched into television production, understands the importance of rewriting history as much as anyone. But for all the praise he’s given throughout the documentary from the likes of Jay-Z and Nas, renowned hip-hop execs like Lyor Cohen and Steve Stoute, and Murder Inc. artists and former employees, there’s also a consistent, honest critique of how Gotti often got in his own way. There is much redemption to be found throughout the episodes, but in each one, the underlying takeaway is that, visionary or not, Gotti was often his worst enemy.

Charli Baltimore recounts the label head’s inconsistencies, explaining how depending on the day you approached him, you either got “sober Gotti” or one high on drugs. Then there’s the matter of his mouth. Nearly every contributor at one point highlights that Gotti’s bluntness created unnecessary problems for him. Drugs and bluntness would hinder anyone’s management capabilities, but what further complicated Gotti’s run of Murder Inc and its legacy is his handling of Ashanti, then and now. Even today, he refuses to change his perspective, update with the times, or offer what would’ve made this the ultimate redemption story: remorse.

In episode three, Gotti describes how he and Ashanti started a relationship around the same time his wife put him out of the house for infidelity. That same episode reminds us of his success as a producer and label head. “Irv had the Number One record in the country for 48 weeks during that time — which is unheard of,” Terry Herbert, manager at Crack House Studios, explains. Gotti’s brother, Chris Lorenzo, who served as Vice President of Murder Inc Records, puts the point in even sharper focus. “You know, Irv is the Guinness Book for the longest run of Number One records as a producer.” These are the two sides of Gotti: radical and self-destructive.

The label suffered its share of ups and downs — including its feud with 50 Cent and G-Unit Records. Murder Inc’s offices were then raided in 2003 after the label was accused of being a money-laundering front for Kenneth “Supreme” McGriff of Queens’ legendary Supreme Team. After a three-year legal fight, Gotti was acquitted by a federal jury, but as it’s explained in the final episode, the battle effectively left Gotti depleted and forced to take a “sabbatical” from the industry.

It wasn’t just 50 Cent and the federal government that did him in, though — it was also, apparently, drugs. “He was so high,” Angie Martinez recounts at one point. “I was so mad at him. Like, what are you doing? This can’t be your life.” Other commentators in the doc quip that ecstasy might have been the inspiration behind Ja Rule and Ashanti’s Grease-inspired video for “Mesmerize” — an explanation that makes sense. Beyond the drugs, nearly every contributor cites Gotti’s mouth and fiery comments getting him in trouble.

The series ultimately makes for a good victory lap — which Gotti botches by whining about an employee who stopped wanting to date him more than a decade ago. Consenting adults are free to do as they please, but Gotti, then head of his label and 30-plus years old, speaks at length about falling in love with Ashanti while estranged from his then-wife. In the docuseries, as he did on Drink Champs, Gotti shares the anecdote about creating the melody for Ashanti’s 2002 single “Happy” in the shower after a night together. In episode four, he brags about how Ashanti wrote records like “Rock Wit U” to impress him.

None of it sounds as romantic as Gotti makes it — as evidenced by Ashanti’s lack of involvement in the series. Not to mention the relationship’s impact on other artists on Gotti’s roster. Charli Baltimore, who joined the label in 2002, speaks of Gotti’s “laser focus” on Ashanti. And Vita, who says she has no ill will towards Ashanti but felt distant from her, also expresses her frustrations with Gotti. “None of us really made it but Ashanti and Ja.”

At the end of the docuseries, Gotti shares that he inked a $300 million deal with Iconoclast, an international network servicing global agencies, music labels, and content platforms. “I’m signing a deal worth $300 million," Gotti revealed earlier this summer. The deal includes $100 million for his stake in the masters he shares 50 percent ownership with Universal Music Group and access to a $200 million line of credit to produce and create television and film projects.

For a man who spent a fortune fighting the federal government for his freedom only to lose the spark he had for music, that’s quite a turnaround. After being written off so many times, Gotti is right to beat his chest about where he landed. When asked why he’s kept talking about Ashanti in interviews, Gotti told The Shade Room at this year’s MTV VMAs: “If I didn’t talk about Ashanti, you would’ve been like, ‘What type of bullshit is that? He didn’t speak about [Ashanti]? She’s too important to Murder Inc and his life.’”

It isn’t the subject itself but the way Gotti talks about Ashanti that’s the problem, of course, and it’s a shame he’s so oblivious because her absence from the docuseries leaves a noticeable void. Gotti pledged to stop bringing her name up in a comment on The Shade Room. “It’s gonna be NO COMMENT from here on end. Hahah. But I felt like at least trying to make y’all understand,” he wrote. “Moving forward. It will be limited interviews and about of no comments. I tell the truth cause I want the People to know the real. But honestly. Y’all don’t give a fuk about the truth.”

While The Murder Inc Story does portray an incredible rags-to-riches story, if it’s redemption that Gotti seeks, he’ll have to take comfort in the music he produced so many years ago still resonating at events like Verzuz and the live shows Ja Rule and Ashanti continue to perform. Gotti is as much a loudmouth as a visionary whose tactless approach to revisiting his glory days has ironically made him look like what he never wanted to be: a typical, cliché music executive.